A Paris Photo, tout le monde parle de photos. Analyse critique, commentaire, contextualisation : la photographie peut-elle se passer des mots ?

Ajuster son regard

pour ne pas passer à côté des oeuvres.

Chaque année, Paris Photo concentre plusieurs milliers de photographies appuyées par des centaines de démarches différentes. Le spectateur, lui, est soumis à la nécessité d’adapter son regard d’un stand à l’autre, de constamment ajuster sa mire pour que la compréhension de ce qu’il a devant les yeux n’atterrisse pas à l’écart de la cible.

Dans les stands, se pose alors de manière aigüe la question du discours qui accompagne les oeuvres. Une question que le béotien trop sûr de lui écarte rapidement avec des arguments aussi pointus que « moi, je marche à l’émotion » ou bien « il y a des photos qui me parlent et d’autres qui ne me parlent pas » (notons au passage que considérer que ça parle, c’est bien redonner une forme de prééminence au discours). Parfois, c’est l’artiste lui-même qui conforte le spectateur dans cette conception du discours comme commentaire superfétatoire avec le trop fameux : « si j’avais voulu dire les choses avec des mots, j’aurais été écrivain plutôt que photographe ». Autant de refrains qui mettent dans le même sac contextualisation, clefs d’entrée dans l’oeuvre, commentaire, analyse critique ou historique, dans le but de secondariser le langage par rapport au visuel.

C’est avec cette problématique du discours sur les oeuvres que notre chroniqueuse Silvy Crespo a inlassablement arpenté les allées de Paris Photo cette année.

Si Paris Photo est une foire donc, par définition, une manifestation commerciale périodique dont l’objectif premier est la vente d’objets photographiques, il est possible de se demander si la valeur de ces objets ne repose que sur leur esthétisme. En d’autres termes, qu’advient-il du propos de l’artiste dans le contexte d’une foire ?

En quête d’explications

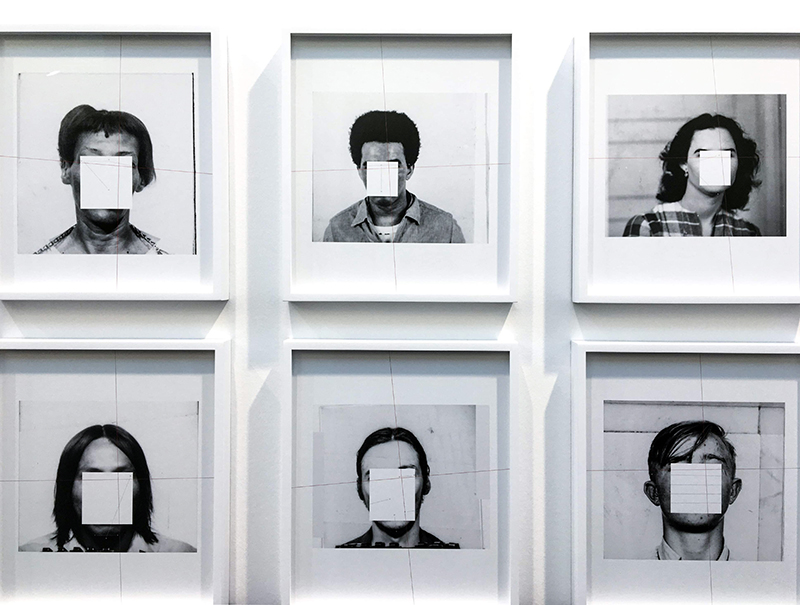

Je me suis posée la question après avoir repéré, accrochés sur un mur blanc, sans aucune autre information que celles mentionnées sur le cartel, les portraits anonymes de Trevor Paglen appartenant à la série intitulée « They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead ». Cela fait quelque temps que je suis le travail de cet artiste qui traite notamment des images computationnelles. Ici, après avoir tenté de décrypter les images je comprends qu’il est question de données anthropométriques. Un détail m’échappe cependant : la présence d’une ligne rouge dont je ne sais s’il s’agit d’un choix purement esthétique ou s’il est au, contraire, justifié par un élément particulier.

Frustrée par cette incompréhension, mais surtout par le manque d’un minimum d’information permettant de comprendre au moins brièvement ce qui m’est donné à voir, je m’aventure à demander à la galeriste un peu plus d’explications sur la présence de cette ligne rouge. Je lui précise que j’ai bien compris qu’il s’agit de mesures faciales et que ma question porte vraiment sur ce détail, plutôt esthétique au demeurant. Après cinq minutes de tentatives d’éclaircissements, dont il ressort que l’artiste a utilisé une technologie avancée de reconnaissance faciale employée par le gouvernement américain, je repars toujours aussi ignorante quant à cette fameuse ligne rouge dont je persiste à croire qu’elle n’est pas là pour rien.

Des objets esthétiques vidés de leur propos ?

Quelques stands plus loin, un photogramme expérimental accroche mon regard. Ce n’est pas tant le sujet de la photographie que le procédé utilisé par le photographe qui m’interpelle cette fois-ci. Là encore, je me tourne vers la galeriste qui ne tente même pas une explication et ajoute que l’artiste ne sait pas trop et que d’ailleurs, il affirme avoir perdu le négatif !

L’acheteur/collectionneur ou le simple visiteur ne seraient-ils que des esthètes n’ayant que peu d’intérêt pour le message latent de l’œuvre et la démarche de l’artiste ? Le fondement marchand de la foire dispenserait-il le galeriste de la nécessité de contextualiser le travail des artistes ? Suffirait-il, comme pour l’achat d’une paire de chaussures, de renseigner la taille, la matière et le prix ?

Contextualiser l’oeuvre,

Percevoir les couches de sens

Agitée par cette question, je m’arrête sur le stand d’une galerie berlinoise (Feldbusch Wiesner Rudolph) représentant l’artiste Sara-Lena Maierhofer dont la série « The Object Remains » m’intéresse particulièrement (voir la vidéo sur l’Insta de Viens Voir). Ici, outre la possibilité d’échanger longuement avec l’artiste elle-même sur la technique d’impression utilisée, je me vois remettre par la galeriste un livret d’explications permettant de comprendre l’ensemble de la problématique abordée par Sara-Lena, ainsi que le procédé photographique employé.

Autre belle surprise sur le stand exposant le travail de Nicola Lo Calzo puisque dans le cas de ce dernier, un espace est réservé à une vitrine accueillant des ouvrages variés qui forment une partie de la recherche théorique de l’artiste dans le cadre de la réalisation de son projet photographique au long cours. Un échange avec la galeriste montre que cette dernière connaît parfaitement le travail de l’artiste qu’elle représente. Ici une belle image ne se regarde pas (ne se comprend pas) indépendemment de son propos.

Certes, une certaine catégorie d’oeuvres se passe aisément de discours ou d’élements contextuels. Mais ce sont souvent celles qui offrent une séduction immédiate ou cèdent à une forme de spectacularité. Pénétrer dans le travail de l’artiste, dans la profondeur d’un processus de création, ce n’est certainement pas pallier une faiblesse de l’oeuvre : c’est au contraire en dessiner le champ d’action et en établir les strates de sens. La noblesse du galeriste réside aussi dans cette partie du soutien aux photographies.

Cet article est cosigné par Silvy Crespo et Bruno Dubreuil

- Paris Photo : parisphoto.com

- Sara-Lena Maierhofer : saralena.com

Why discourse on the photos?

Adjusting your gaze,

so as not to miss the works

Each year, Paris Photo concentrates several thousand photographs supported by hundreds of different approaches. The spectator, on the other hand, is subject to the need to adapt his gaze from one stand to another, to constantly adjust his sight so that the understanding of what is in front of his eyes does not land away from the target.

In the stands, the question of the discourse that accompanies the works is then acutely raised. A question that the self-assured philistine quickly dismissed with arguments as sharp as « I follow my emotions » or « there are photos that talk to me and others that don’t talk to me » (let’s note that considering that it talks is to give back a form of pre-eminence to the words). Sometimes it is the artist himself who reassures the spectator in this conception of the discourse as a superfluous commentary with the too famous: « if I had wanted to say things with words, I would have been a writer rather than a photographer ». So many choruses that put in the same bag contextualization keys to entering the work, commentary, critical or historical analysis, in order to secondarize language in relation to the visual.

It is with this problem of the discourse on works that our columnist Silvy Crespo has tirelessly walked the alleys of Paris Photo this year.

If Paris Photo is a fair and therefore, by definition, a periodic commercial event whose primary objective is the sale of photographic objects, it is possible to wonder whether the value of these objects is based solely on their aesthetic appeal. In other words, what happens to the artist’s point in the context of a fair?

In search of explanations

I asked myself the question after having identified, hung on a white wall, without any information other than those mentioned on the cartel, the anonymous portraits of Trevor Paglen belonging to the series entitled « They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead ». I have been following the work of this artist for some time now, who deals with computational images in particular. Here, after having tried to decrypt the images, I understand that it is a question of anthropometric data. However, one detail escapes me: the presence of a red line, which I do not know if it is a purely aesthetic choice or if it is, on the contrary, justified by a particular element.

Frustrated by this misunderstanding, but especially by the lack of a minimum of information allowing me to understand at least briefly what I have to see, I venture to ask the gallery owner for a little more explanation on the presence of this red line. I would like to point out to her that I have understood that these are facial measurements and that my question really concerns this detail, which is rather aesthetic in fact. After five minutes of attempts at clarification, which show that the artist used an advanced facial recognition technology used by the American government, I still leave as ignorant as ever about this famous red line, which I still believe is not there for nothing.

Aesthetic objects emptied of their purpose?

A few stands further on, an experimental photogram catches my eye. It is not so much the subject of the photograph as the process used by the photographer that appeals to me this time. Here again, I turn to the gallery owner who doesn’t even try to explain it and adds that the artist doesn’t know too much and that, moreover, he claims to have lost the negative!

Contextualize the work

Perceive the layers of meaning

Would the buyer/collector or the simple visitor only be aesthetes with little interest in the latent message of the work and the artist’s approach? Would the commercial basis of the fair exempt the gallery owner from the need to contextualize the artists’ work? Would it be sufficient, as with the purchase of a pair of shoes, to provide information on size, material and price?

Agitated by this question, I stop at the stand of a Berlin gallery (Feldbusch Wiesner Rudolph) representing the artist Sara-Lena Maierhofer whose series « The Object Remains » interests me particularly (see the video on the Insta de Viens Voir). Here, in addition to the opportunity to discuss at length with the artist herself about the printing technique used, I am given by the gallery owner a booklet of explanations allowing me to understand the whole issue addressed by Sara-Lena, as well as the photographic process used.

Another nice surprise on the stand exhibiting Nicola Lo Calzo’s work since, in the latter’s case, a space is reserved for a showcase featuring various works that form part of the artist’s theoretical research as part of the realization of his long-term photographic project. An exchange with the gallery owner shows that she is perfectly familiar with the work of the artist she represents. Here a beautiful image is not viewed (understood) independently of its purpose.

Certainly, a certain category of works can easily do without speeches or contextual elements. But they are often the ones that offer immediate seduction or give way to a form of spectacularity. To penetrate into the artist’s work, into the depth of a creative process, is certainly not to compensate for a weakness in the work: on the contrary, it is to draw its field of action and establish its layers of meaning. The nobility of the gallery owner also resides in this part of the support for the photographs.

This article is co-authored by Silvy Crespo and Bruno Dubreuil

- Paris Photo: parisphoto.com

- Sara-Lena Maierhofer: saralena.com