Précédemment :

Les propriétés supposées de la photographie objective.

L’écriture photographique prend parfois une forme dite objective, c’est-à-dire neutre, froide, distante, qui semble restituer le monde comme si le photographe s’était livré à un pur enregistrement. Cette écriture n’en est pourtant pas moins une manière de dire le monde, ce qui infère qu’elle soit articulée comme un langage.

Nous allons tenter prudemment de caractériser ce que serait une photographie objective et d’en déduire ses propriétés, en opposition à une photographie perceptive.

1. Une photographie objective ne déforme pas = elle laisse aux choses leur propre forme, alors que dans la photographie perceptive, c’est l’oeil du photographe qui in-forme, utilisant au besoin les caractéristiques techniques de la machine photographique. Entre autres conséquences, la photographie objective est rectiligne, elle ne saurait pencher (elle fait donc l’heureuse économie de cette petite idée selon laquelle pencher une photo pourrait la dynamiser).

Une image impartiale

2. Une photographie objective détaille toutes les parties de l’image avec la même précision et étale le visible sur l’ensemble de la surface = en elle, tout se distingue équitablement, rien n’est particulièrement souligné ; pas de hiérarchie entre les différents éléments qui se pourrait se manifester, par exemple, entre les parties nettes et les parties floues. Une photographie objective se veut impartiale.

3. Une photographie objective est frontale = face à celui qui regarde, le monde ne se présente pas de biais mais dans un face-à-face direct. Une esthétique qui reprend les termes d’une confrontation avec le réel plutôt que de contourner les apparences pour passer derrière le rideau de la surface, pénétrer la chair du monde.

Ne pas trancher dans le réel

4. Une photographie objective évite de couper le réel trop brutalement. C’est-à-dire qu’elle n’ampute pas le réel pour créer une forme (comme le fait René Burri dans l’exemple ci-dessous, appuyant la perception du photographe) ou évoquer puissamment un hors-champ = elle prend pour postulat une continuité du monde plutôt qu’une discontinuité qui l’instaurerait comme fragmentation possiblement métonymique. Une photographie objective laisse autant que possible entières les formes qu’elle montre.

5. Une photographie objective organise une entrée dans l’image : nul besoin d’enjamber un cadre pour mettre un pied dans le monde (comme le nécessite la photo de Gary Winogrand présentée dans l’article précédent), ce qui accuserait la nature photographique de l’image (nous, spectateurs, serions face à une photo plutôt que face au monde).

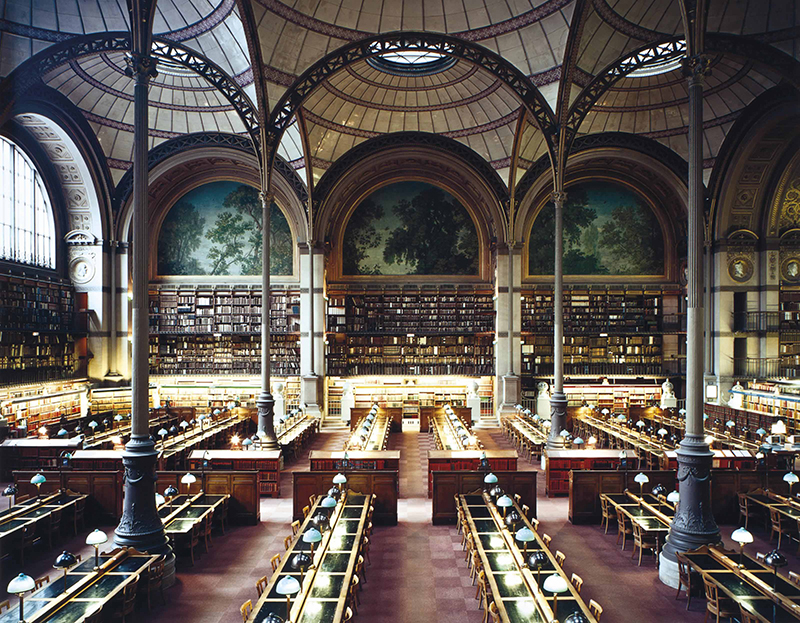

6. Des points 4 et 5 découle le fait qu’une photographie objective calcule sa distance à ce qu’elle regarde, embrassant large lorsqu’il s’agit d’un paysage, ne cadrant pas trop serré lorsqu’il s’agit d’un corps. Cette photographie objective entretient d’ailleurs dans son rapport au réel une véritable dimension anthropologique. Observons ainsi comme la photo de Une de Candida Höfer respecte une parfaite symétrie centrale, un des traits les plus saillants (et anciens) de la quête artistique de l’animal humain.Observons aussi comme cette dimension rejoint un code culturel qui est devenu notre norme, celui de la perspective centrale.

7. La lumière d’une photographie objective ne doit pas être trop expressive, ajoutant des ombres portées qui travailleraient le volume ou la surface de la photo.

La transparence ne garantit pas la présence

8. Conclusion. La photographie objective semble n’avoir rien d’autre à dire que ce qu’elle montre = choses, êtres, évènements, elle ne les interprète pas mais les laisse parler tels qu’ils sont en eux-mêmes, comme par transparence. De cette attitude non discursive s’élabore souvent dans les commentaires une sorte d’esthétique de la Présence, une idée un peu mystique et lègèrement arbitraire : car bien sûr, il ne saurait exister une manière de photographier capable de garantir la présence de ce qui est montré sur l’image.

De l’intérêt de la nuance

Il nous faut avancer deux points pour modérer cette analyse :

1. On aura noté dans mon texte un glissement du présent de l’affirmation à l’emploi du conditionnel. C’est qu’il s’agit ici surtout de comprendre les propriétés associées à ces choix plutôt que de les énoncer de manière dogmatique. Ces propriétés peuvent et doivent être questionnées.

2. Ces propriétés, aussi limitatives soient-elles, n’excluent pas les nuances. A vrai dire, c’est même là que niche tout l’intérêt de la règle. Prenons l’exemple de la lumière qualifiée précédemment de pas trop expressive : les photographies objectives sont pourtant loin de présenter toutes le même type de lumière. Ainsi, certaines lumières, en apparence neutres, sont en fait très précises et finement adaptées à l’ambiance que veut saisir le photographe.

La stratégie de l’objectivité

Mais surtout, la supposée transparence de la photographie objective n’est qu’une stratégie. Car la photographie objective est bien fabriquée par un appareil photo (la chambre photographique est souvent privilégiée), et un auteur qui pense et choisit. En ce sens, l’impartialité de la photo, feinte ou réelle, ne dissimule pas vraiment l’intentionnalité du photographe.

A celui-ci de jouer des codes…

À suivre :

Assumed properties of objective photography (2/3)

Photographic writing sometimes takes on a neutral, cold, distant form, which seems to render the world as if the photographer had indulged in pure recording. Yet this writing is nonetheless a way of telling the world. So to be articulated like a language.

Let us attempt with caution to characterize what an objective photograph would be and to deduce its properties, as opposed to a perceptive photograph.

1) An objective photograph does not distort = it leaves things with their own form, whereas in perceptive photography it is the eye of the photographer that shapes, using if necessary the technical characteristics of the photographic machine. Among other consequences, objective photography is rectilinear, it cannot tilt (it therefore makes the happy economy of this small idea according to which tilting a photo could energize it).

2) An objective photograph details all the parts of the image with the same precision and spreads the visible over the whole surface = in it, everything stands out equally, nothing is particularly emphasized; no hierarchy between the different elements that could arise, for example, between sharp and blurred parts. An objective photograph is meant to be unbiased.

3) An objective photograph is frontal = facing the viewer, the world does not appear biased but in a direct face-to-face. An aesthetic that takes up the terms of a confrontation with the real rather than bypassing appearances in order to pass behind the curtain of the surface, to penetrate the flesh of the world.

4) An objective photograph avoids cutting the real too abruptly; that is to say, it does not amputate the real in order to create a form (René Burri in the example below) or powerfully evoke an off-screen = it takes as a postulate a continuity of the world rather than a discontinuity that would establish it as a possible metonymic fragmentation. An objective photograph leaves the forms it shows as whole as possible.

5) An objective photograph organizes an entry into the image : there is no need to step over a frame to set foot in the world (see Winogrand photo in the previous article), which would blame the photographic nature of the image (we, the spectators, would be facing a photo rather than the world).

6) From points 4 and 5 flows the fact that an objective photograph calculates its distance from what it is looking at, embracing wide when it is a landscape, not framing too tightly when it is a body.

7) The light in an objective photograph should not be too expressive, adding drop shadows that would work on the volume or surface of the photo.

8) Conclusion.

Objective photography seems to have nothing else to say than what it shows = things, beings, events, it doesn’t interpret them, it lets them speak as they are in themselves, as if by transparency. From this non-discursive attitude a kind of aesthetics of the Presence is often elaborated in the commentaries, a somewhat mystical and slightly arbitrary idea: for of course, there cannot be a way of photographing that is capable of guaranteeing the presence of what is shown in the image.

Several points to moderate this analysis:

1) One will have noted in my text a shift in the present tense from the affirmation to the use of the conditional. This is because it is mainly a question of understanding the properties associated with these choices rather than stating them dogmatically. These properties can and must be questioned.

2) These properties, however limiting they may be, do not exclude nuances. In fact, this is where the interest of the rule lies. Let’s take the example of light: objective photographs are far from all presenting the same type of light. And some lights, apparently neutral in appearance, are in fact very precise and finely adapted to what the photographer wants to show.

But above all, the supposed transparency of objective photography is only a strategy. Because objective photography is well made by a camera (the photographic chamber is often privileged), and an author who thinks and chooses. In this sense, the impartiality of the photo, feigned or real, does not really hide the intentionality of the photographer.

It is up to the photographer to play with codes…

This will be the subject of our third and last part