Précédemment :

- 1ère partie : Analyse des caractéristiques de la photographie objective et subjective

- 2ème partie : Les propriétés supposées de la photographie objective

Les propriétés d’une photographie subjective ou objective étant plus précisément définies, reste à savoir pourquoi et comment les utiliser ?

Réponse avec l’analyse de deux images de Philip-Lorca diCorcia et Jeff Wall.

Et maintenant que tu connais les codes, tu peux les intégrer à ta manière de photographier, les exploiter ou les détourner. Pas pour faire semblant, non, tu ne fais pas semblant. Mais pour écrire.

Car c’est ça que tu fais quand tu photographies : tu écris.

La photographie

comme texte visuel

Ce que tu crées dans tes photos, c’est un texte visuel qui se déploie à l’intérieur du cadre. Pointant un élément avec une précision presque douloureuse ou estompant le visible à grands coups de flou. Dans certaines images, tu concentres les choses ; dans d’autres, tu les exiles aux lisières de l’image, à la limite d’en sortir, de basculer au dehors.

Tu vois, mais pas tout.

Tu calcules, mais pas tout.

Tu organises le monde, mais tu le laisses aussi, toujours, te dépasser. Dépasser tes intentions.

Tu ne crées pas des systèmes ou des théories.

Tu es un poète. A travers tes photographies, une lecture du monde devient possible.

Tu as intégré les codes dans ta manière de photographier, peut-être ne les vois-tu même plus. Ou bien ne sont-ils pour toi qu’un outil, au même titre que le matériel que tu choisis pour construire tes images.

Voyons ça.

Recréer une approche subjective

Supposons que tu aies envie de photographier des moments de l’intimité familiale, mais que tu les mettes en scène. Pourquoi ? Justement pour qu’elles aient l’air de ressembler à la réalité captée de manière directe, brute. Seulement, l’expérience t’a appris que ces photos-là, saisies sur le vif, échouent souvent à porter l’épaisseur de l’instant perçu. Alors, il faut recréer la réalité, presque pour qu’elle coïncide mieux avec elle-même. Eventuellement lui ajouter quelques détails supplémentaires, pas totalement inventés mais qui, peut-être n’étaient pas à cet endroit précis, ou y étaient à un autre moment. Ton travail de photographe, dans l’élaboration de l’image, commence à ressembler à celui d’un écrivain qui transpose, cristallise, synthétise. Proust raconte ça très bien : il n’utilise que des éléments vrais, vécus, mais qu’il recompose pour former la matière du roman.

C’est là que tu as besoin des codes, ceux de la photographie subjective. Ainsi, tu sais qu’on entre dans une image par la gauche (suivant ainsi notre sens de lecture des mots) et que cette portion de porte présente plusieurs propriétés subjectives : le flou de mise au point, l’aberration optique de ce qui est vu à travers le verre. Tout indique que la porte vient d’être poussée à l’instant, confondant photographe et spectateur dans un même geste/regard, indiquant surtout que la scène présentée est saisie par surprise, alors que c’est l’inverse exact de la réalité de la fabrication de cette photo.

Une maladresse calculée

Il y a plus encore : que vise donc à montrer cette photo ? Une femme en train de repasser ? Mais alors la photo est maladroite, puisque le montant de la porte recouvre précisément la main qui tient le fer, une maladresse qui renforce la spontanéité apparente de l’image. Nous croyons donc être positionnés face à un document direct : la photo peut maintenant déployer ses micro-histoires : qui est cette femme, quelle vie lui imagine-t-on, pourquoi ne porte-t-elle qu’une seule chaussure ? Les cadeaux sur le coin du canapé laissent-ils entendre que nous sommes face à l’envers du décor d’une fête familiale ? Des indices qui, dans cette scène du quotidien, invitent le spectateur à tisser des fils narratifs.

Ou bien.

Une photographie objective ?

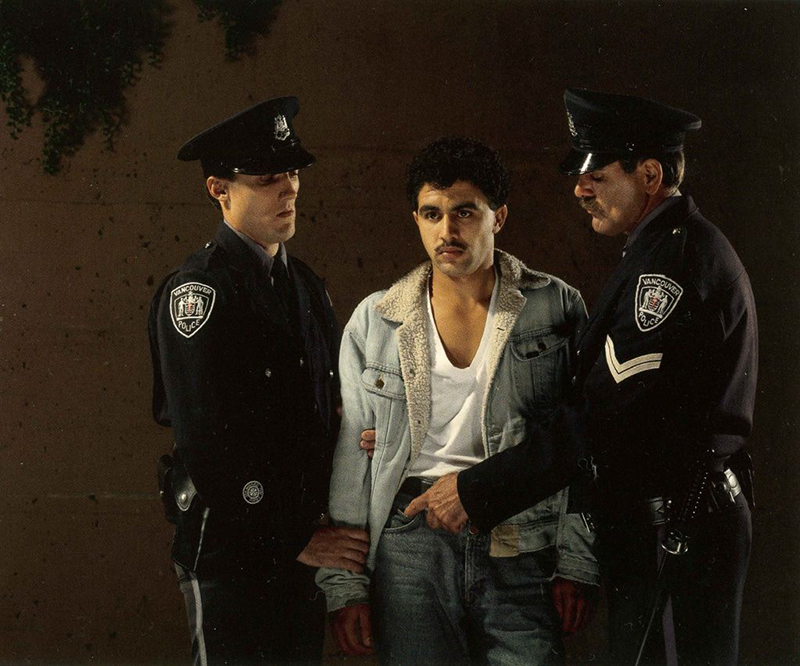

Tu pratiques plutôt une photographie dite objective. Cette fois, tu n’es pas entré dans la pièce soudainement, comme par effraction. Rien dans ton image n’indique une composition faite à la hâte. Pas de coupe sauvage ou de chevauchement intempestif, tu as pris le temps de réfléchir à ton cadre, en prenant suffisamment de recul afin de ne pas gêner ton modèle. Pas d’ombre ou de lumière trop forte, pas de clair-obscur caravagesque entraînant la photographie du côté d’une peinture allégorique (voilà encore un code), comme on peut le trouver aussi dans certaines de tes photos, par exemple celle ci-dessous.

Mais dans la photo représentant Adrian Walker, il y a plutôt une sorte de neutralité, d’atonalité, qui installe l’image dans une forme de réalisme. Là aussi, nous pouvons attribuer à cette photo une qualité documentaire. Et justement, le titre appuie ce positionnement documentaire en renseignant le protagoniste, l’action et le lieu.

Se produit donc bien cette forme de transparence que nous avons souvent évoquée à propos de la photographie objective. Le photographe n’y expose aucun savoir-faire particulier, il disparait au profit de la scène captée.

Un autre temps pour la photographie

A vrai dire, là aussi, la photo aurait pu être prise fortuitement, même si on sent confusément que quelque chose cloche : plutôt que du côté de l’instantanéité, l’image marque un temps d’arrêt, une suspension du temps. Le personnage est absorbé dans ses pensées, dans un temps de réflexion devant le sujet qu’il dessine (peut-être au même instant, es-tu toi-même absorbé devant ce sujet que tu t’apprêtes à photographier).

Ce temps qui s’arrête et s’étire ouvre une voie parallèle à celle de la conception classique de la photographie comme mouvement figé et éternisé dans sa pose. Elle n’oppose pas une photographie de la théâtralité (mise en scène) à une photographie plus directe : elle adopte une partie des apparences de celle-ci pour inventer celle-là*.

Pourtant, à bien y réfléchir, cette photographie, si elle ne se révèle pas dans une épiphanie lumineuse, ne se présente pas non plus dans une parfaite clarté documentaire : le corps du personnage est tourné de telle manière que son visage nous est en grande partie caché (comme le sont ses pensées). Le dessin se présente de biais si bien que la perspective est difficile à apprécier (notons que cette perspective raccourcie est une des difficultés majeures du dessin anatomique). De cet homme et des raisons qui l’amènent à pratiquer cette activité en ce lieu, nous ne savons rien d’autre que ce que nous transmettent les informations du titre. Pourquoi s’extrait-il du monde réel pour s’abîmer dans celui de la représentation ? Et l’objet de la représentation, celui qui appartient au monde réel, n’est-il pas lui-même le représentant d’un monde mort, momifié ?

S’approprier le réel

On comprend à présent que tu t’es servi des apparences du réel (la fameuse transparence) pour construire une fiction flottante, support d’une réflexion esthétique et philosophique. Cette manière d’opérer, tu appelles ça le « presque documentaire », une expression assez géniale tant elle met en place, non la fiction (ou une presque fiction), mais l’écart entre le réel brut et sa mise en forme, comme une condition de sa compréhension et de son appropriation.

Nous pourrions alors prolonger notre texte d’introduction :

A travers tes photographies, une lecture du monde devient possible.

Tu as intégré les codes dans ta manière de photographier, peut-être ne les vois-tu même plus. Ils ne sont devenus pour toi qu’un outil, au même titre que le matériel que tu choisis pour construire tes images. Tout cela participe de ton langage photographique, et ce qui compte, c’est la question qui précède la mise en mouvement : comment se positionner dans ou devant le monde afin d’en rendre compte ?

* Toute cette conception de la photographie est remarquablement théorisée dans plusieurs ouvrages de Michael Fried, particulièrement dans Pourquoi la photographie a aujourd’hui force d’art (Hazan, 2013)

Photography: the codes of objectivity and perception (3/3)

The properties of a subjective or objective photograph being more precisely defined, why and how to use them? The answer with the analysis of two images by Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Jeff Wall.

And now that you know the codes, you can integrate them into your way of photographing, exploit or divert them. Not to pretend, no, you’re not pretending. But to write.

Because that’s what you do when you photograph: you write.

What you create in your photos is a visual text that unfolds inside the frame. Pointing at an element with almost painful precision or blurring the visible with blurred strokes. In some images, you concentrate things; in others, you exile them to the edges of the image, on the verge of coming out of it, of tilting outside.

You see, but not everything.

You calculate, but not everything.

You organize the world, but you also let it always surpass you. Surpass your intentions.

You don’t create systems or theories.

You’re a poet. Through your photographs, a reading of the world becomes possible.

Let’s take a look at this.

Suppose you want to photograph scenes of family intimacy, but you want to stage them. Why would you want to do that? Precisely so that they look like the reality captured in a direct, raw way. But experience has taught you that these photos, taken on the spot, often fail to convey the depth of the perceived moment. So you have to recreate reality, almost to make it coincide better with itself. Eventually adding a few more details, not totally invented but which perhaps weren’t in that particular place, or were there at another time. Your work as a photographer, in the elaboration of the image, begins to resemble that of a writer who transposes, crystallizes, synthesizes. Proust tells it very well: he only uses real, lived elements, but which he recomposes to form the material of the novel.

That’s where you need the codes, those of subjective photography. So you know that we enter an image from the left (following our sense of reading the words) and that this part of the door has several subjective properties: the blur of focus, the optical aberration of what is seen through the glass. Everything indicates that the door has just been pushed at the moment, confusing photographer and spectator in the same gesture/look, indicating above all that the scene presented is captured by surprise, whereas it is the exact opposite of the reality of the making of this photo.

There is more: what is this photo intended to show? A woman ironing? But then the photo is clumsy, since the door jamb precisely covers the hand holding the iron, a clumsiness that reinforces the apparent spontaneity of the image. So we believe we are positioned in front of a direct document: the photo can now unfold its micro-stories: who is this woman, what kind of life do we imagine for her, why is she wearing only one shoe? Do the gifts on the corner of the couch suggest that we are facing the other side of the decor of a family celebration? Clues that, in this everyday scene, invite the viewer to weave narrative threads.

Or else.

Instead, you practice what is known as objective photography. This time you didn’t enter the room suddenly, as if by breaking and entering. There is nothing in your image that indicates a hastily made composition. No wild cuts or untimely overlapping, you took the time to think about your frame, taking enough distance so as not to interfere with your model. No shadows or too strong light, no caravaggio chiaroscuro that leads you to photograph the side of an allegorical painting (here again a code), as can also be found in some of your photos.

But in this one, there is rather a kind of neutrality, a kind of atonality, which installs the image in a form of realism. Here too, we can attribute a documentary quality to this photo. And the title supports this documentary positioning by informing the protagonist, the action and the place.

This form of transparency, which we have often mentioned in connection with objective photography, does indeed occur. The photographer does not expose any particular know-how, he disappears in favour of the captured scene.

To tell the truth, here too, the photo could have been taken by chance, even if one feels confused that something is wrong: rather than on the side of instantaneity, the image marks a pause, a suspension of time. The character is absorbed in his thoughts, in a time of reflection in front of the subject he is drawing (perhaps at the same moment, are you yourself absorbed in front of the subject you are about to photograph).

This time that stops and stretches opens a path parallel to that of the classical conception of photography as movement frozen and eternalized in its pose. It does not oppose a photograph of theatricality (staging) to a more direct photograph: it adopts some of the appearances of the second one to invent the first*.

On reflection, this photograph, if it does not reveal itself in a luminous epiphany, does not present itself in perfect documentary clarity either: the character’s body is shot in such a way that his face is largely hidden from us (as are his thoughts). The drawing is presented at an angle so that the perspective is difficult to appreciate (note that this shortened perspective is one of the major difficulties of anatomical drawing). We know nothing more about this man and his reasons for doing this activity in this place than what the information in the title tells us. Why does he leave the real world and go into the world of representation? And the object of the representation, the one that belongs to the real world, is it not itself the representative of a dead, mummified world?

We now understand that you have used the appearances of reality (the famous transparency) to construct a floating fiction (support of an aesthetic and philosophical reflection). You call this way of working « almost documentary », a rather brilliant expression because it sets up, not the fiction (or an almost fiction), but the gap between the raw reality and its shaping, as a condition for its understanding and appropriation.

We could then extend our introductory text:

Through your photographs, a reading of the world becomes possible.

You have integrated the codes into your way of photographing, perhaps you no longer even see them. They have become only a tool for you, just like the material you choose to construct your images. All this is part of your photographic language, and what matters is the question that precedes the setting in motion: how to position yourself in or in front of the world in order to tell it?

* All this conception of photography is remarkably theorized in several works by Michael Fried, particularly in Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before.