Un matin de décembre, dans l’atelier de Patrice Pantin : plongée dans les eaux profondes de l’art, le vrai.

(English version included below)

Soyons clair : ce n’est pas de la photo. Ça y ressemble fichtrement, mais ça n’en est pas. C’est même peut-être pour ça que je me suis senti attiré par ce travail au premier regard. Pour la subtilité du décalage avec une forme d’hyperréalisme photographique. Pour ce trouble. Cette envie de passer la main sur l’image pour sentir la texture, pour éprouver qu’elle n’était qu’une image. Comme l’enfant qui croit pouvoir attraper le reflet du monde à la surface du miroir.

La première fois que j’ai rencontré l’oeuvre de Patrice Pantin, c’était sur le salon Drawing Now. Il faut vous dire que ce salon est toujours un de mes plus beaux rendez-vous de l’année. Il y a là tant d’oeuvres qui me font croire que l’action humaine la plus indispensable consiste à prendre un crayon et à tracer des lignes, que j’en sors avec une foi artistique à chaque fois revivifiée.

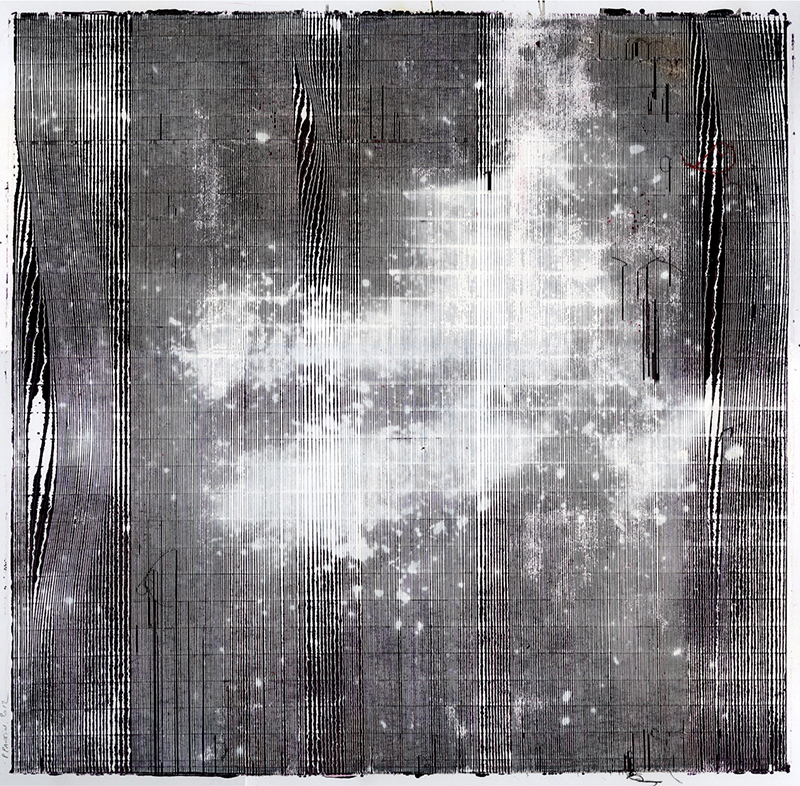

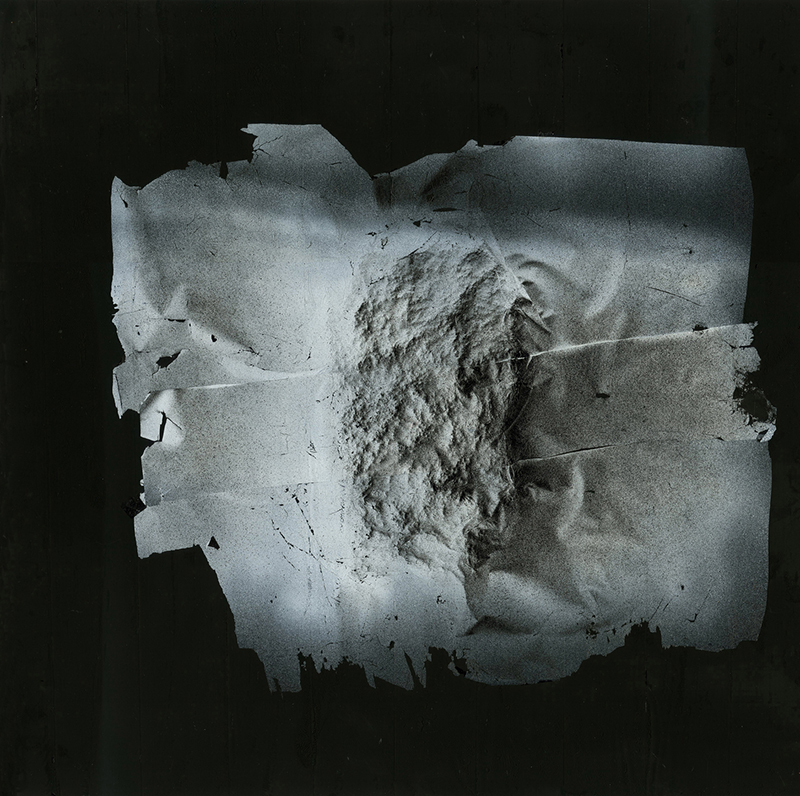

J’avais posé une question à Patrice Pantin, il avait ouvert un carton à dessin. Agenouillés sur la moquette, nous avions regardé ces empreintes fragiles et évoqué le processus de leur création. J’avais dû poser les mêmes questions à plusieurs reprises tant je n’étais pas sûr de bien comprendre. Il avait fait ce geste que je devais revoir plusieurs fois par la suite : celui de Sainte Véronique tenant le voile ayant servi à essuyer la face du Christ, laquelle s’était imprimée sur le tissu. Entre ses pouces et index, les autres doigts écartés en éventail, il tenait un linge invisible, qu’il déplaçait avec délicatesse. Le mystère restait entier, nous avions convenu de nous revoir.

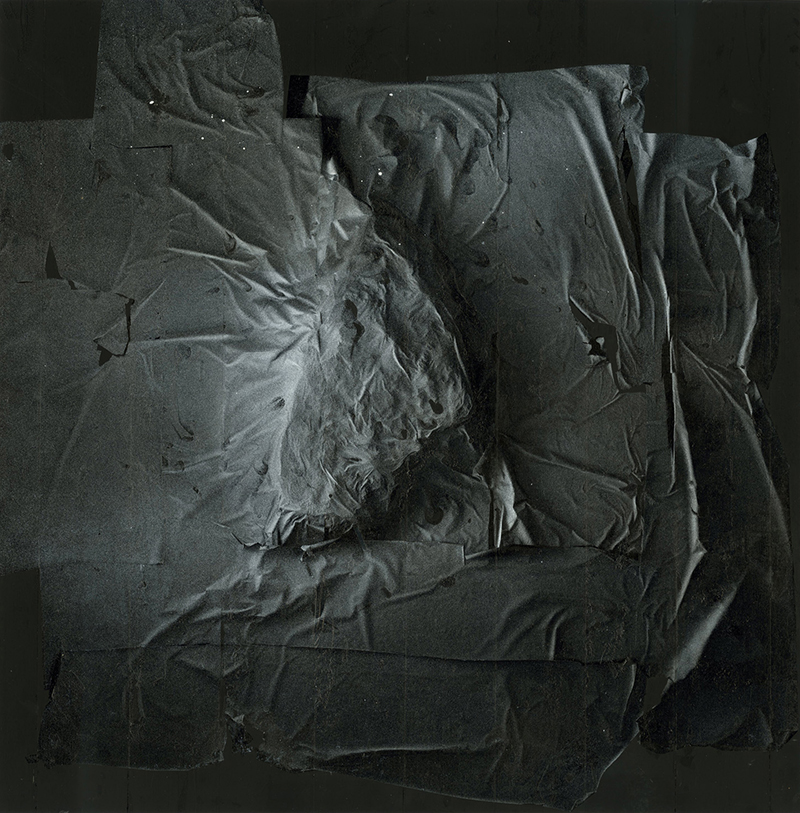

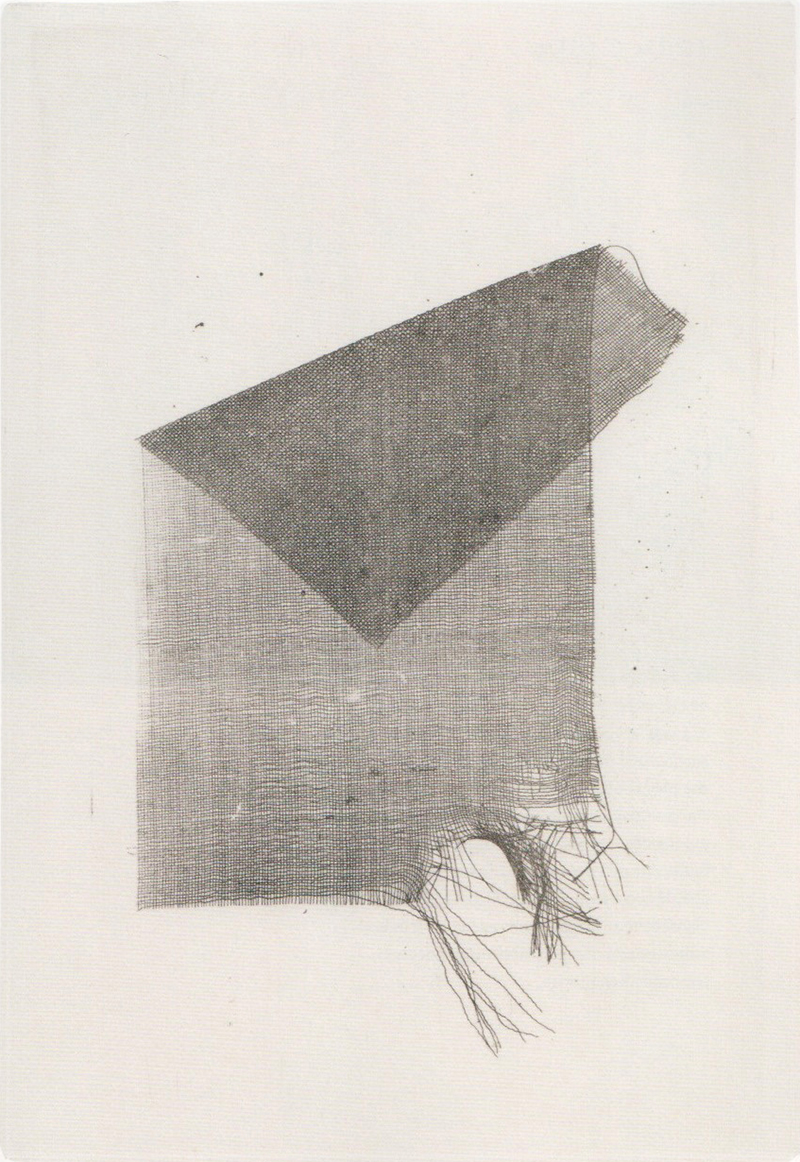

Alors, quelques mois plus tard, je montais les trois marches qui menaient à son atelier, une pièce tout en longueur. « Ici, c’est comme un sous-marin, sur plusieurs étages » me dit-il. Nous nous sommes penchés sur de grandes feuilles constellées d’impacts. Patrice parlait de tissu pictural et c’était le mot juste, puisque le dessin incisait la trame des fils de scotch entoilé qui avait recouvert la toile.

Le mode de fabrication, le processus, Patrice n’en parlait qu’avec retenue. Il ne voulait pas que ce soit révélé, ni même que ce soit au coeur du regard du spectateur. Ce qu’il voulait, c’était chercher en dessinant. « Il y a dans mes images quelque chose qui se planque, quelque chose qui est absent ». Il a cité Magritte : « je ne cherche pas l’invisible, je cherche le visible caché » Il était question de dessiner avec du sable, dessiner au cutter, au rouleau, et même au chalumeau ! « Les images, je les travaille à l’aveugle. Je recouvre tout puis je chauffe au chalumeau. Et ensuite, j’épluche le dessin ». J’effleurai les images de la paume de la main pour en sentir la granulosité. C’était presque comme toucher de la lumière.

Viensvoir : mais toi, qu’est-ce que tu y vois ?

Patrice Pantin : pour moi, c’est comme un ciel, une constellation. Ça flotte, ça envoie des signaux lumineux, des sonorités, crrouik, zzz…

C’est ça, la peinture ou le dessin : non pas une construction, mais une immersion dans un milieu visuel. Pas que visuel, d’ailleurs : penser à Géricault entouré de morceaux de cadavres tandis qu’il travaillait au Radeau de la Méduse. Le désir de mettre un truc devant ses yeux, de passer des journées entières là, de s’y perdre. Un refuge autant qu’une quête. Une façon d’échapper à un danger en en côtoyant un autre.

Viensvoir : c’est un travail à la fois très minutieux et très lâché.

Patrice Pantin : mon outil de travail, c’est la finesse. Regarde, c’est fin comme de la feuille d’or. Je suis une dentellière, à l’abri des bruits du dehors. J’élabore un processus infiniment patient et à la fin, quand je mets l’allumette, Pschoutt ! Je bouscule la brodeuse qui est en moi ! Je dessine avec la chaleur, quelque chose d’aussi immatériel que ce qu’utilise Bernard Moninot (professeur de dessin à l’Ensba) quand il dessine avec le vent.

Nous avons laissé les dessins pour monter à l’étage : là où s’élaborent les fameuse empreintes.

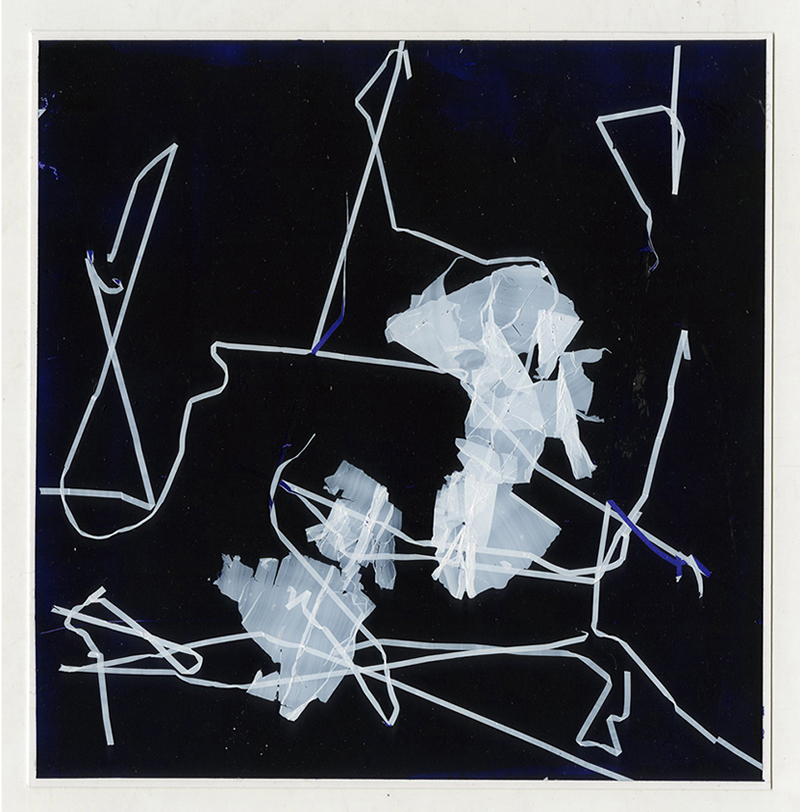

« C’est de la peinture même. Une agglomération de peinture sur de la peinture. » On était en pleine métaphysique. Et en même temps, c’était très concret, très matériel. On palpait des cailloux, des cartons. On parlait même de photo : « le rapport avec la photographie, c’est que dans mes dessins, comme dans la photo, il n’y a pas de repentir possible. J’ai horreur d’un peintre comme Bacon parce qu’il revient sans cesse sur ce qu’il fait, pour améliorer la forme. »

Viensvoir : l’empreinte, le contact, c’est aussi très présent aux origines de la photo : par exemple chez William Henry Fox Talbot, qui appelait ses premières photos des dessins photogéniques.

Patrice Pantin : complètement. Et mes images ont même un coté miroitant, un peu comme le daguerréotype. Il faut les faire jouer devant la lumière pour bien les voir. Ça rappelle aussi les premières images du sol lunaire…

Viensvoir : est-ce que les pierres que tu utilises ont une valeur symbolique ou autobiographique ?

Patrice Pantin : non, ça m’intéresse de partir avec rien. Je travaille avec du caillou pour faire du léger, des pierres qui flottent. Quand je fais une empreinte de pierre, c’est aussi basique qu’un grain de sable. Mais attention, je dis basique au sens où c’est un élément primordial, capable de porter l’infiniment petit et l’infiniment grand, le microcosme et le macrocosme. Il y a une seule empreinte qui est chargée : elle est prise à partir d’une pierre de Malte, que des plongeurs m’ont rapportée. Elle provient d’un haut lieu touristique de l’île de Gozo, l’arche Azure Window, qui s’est effondrée l’année dernière.

Ces empreintes ne sont rien d’autre qu’un voile de peinture pulvérisé sur les choses solides, décollé et positionné ensuite à plat sur une feuille. Quelque chose d’infiniment délicat et volatile, capable de se plier au moindre souffle. Moi j’y vois une sorte de couche intermédiaire du visible. Quelque chose qui rappelle la crainte que la photographie inspirait à Balzac, qui pensait perdre une couche de son être à chaque fois que Nadar prenait son portrait.

Patrice Pantin : Je fais apparaître l’autre face des choses. C’est plein et pourtant c’est vide. Comme nous, comme notre corps : on est du plein et on est aussi beaucoup de vide. Comme la figure du fantôme qui est importante pour moi : une surface visible au dehors, creuse à l’intérieur. Le drap peut tomber au sol et il n’y a plus rien.

Patrice me tend un dernier dessin : « regarde celui-là, il est très près de l’échec. Il y a quelque chose qui se cristallise, mais qui se fissure. »

Cette rencontre intensément poétique s’est terminée sur une image, alors que j’avais demandé à Patrice s’il voyait une origine à tout ça, un moment fondateur. « Quand j’étais gamin, chez ma grand-mère, il y avait ces décalcomanies qu’on devait faire tremper dans un bol d’eau, pour que la pellicule se détache. Elle flottait, il fallait la saisir tout doucement pour la poser sur sa peau… »

Savez-Vous à quoi je reconnais un artiste, un vrai ? Au fait qu’il y a toujours, dans une longue conversation avec lui (ou elle), aussi rôdé que soit le discours sur l’oeuvre (et ce n’est certainement pas le cas de Patrice Pantin), un moment de fêlure. Un blanc. Un doute qui s’engouffre brutalement et le laisse sans voix. Justement, dans notre rencontre, il y a eu ce moment, quand Patrice s’est tourné vers moi : « mais Bruno, dis-moi si tu crois que je me trompe, si tout ça … » Il désignait ses oeuvres et sa main est retombée le long du corps avec une forme d’abattement soudain. Sans cet abîme de doute autour duquel danse l’artiste, il n’y a pas d’oeuvre, que des simulacres.

Le site de l’artiste ici.

Et sa future actualité :

Azur Window, exposition personnelle, Lazuli Art Gallery, Gozo, Malte, mars 2018

MACParis printemps 2018 , Bastille Design Center, Paris. France. 22-27 mai 2018

Dessins: violence et passion du papier. Exposition collective, Gallery 604, Busan, Corée du sud. Mai 2018

« 10 ans déjà au bord de la mer ». Exposition collective, Galerie Réjane Louin, Locquirec, France

English version

Living for pictures

One morning in December, in Patrice Pantin’s workshop: dive into the deep waters of art, the real thing.

Let’s be clear: this is not photography. It looks like a damn thing, but it’s not. Maybe that’s why I felt so attracted to this job at first sight. For the subtlety of offset with a form of photographic hyperrealism. For this disorder. This desire to pass the hand over the image to feel the texture, to feel that it was only an image. Like a child who thinks he can catch the reflection of the world on the surface of the mirror.

The first time I met Patrice Pantin’s work, it was on Drawing Now. I must tell you that this show is always one of my most beautiful events of the year. There are so many works that make me believe that the most essential human action consists in taking a pencil and drawing lines, that I leave with an artistic faith each time revived.

I asked Patrice Pantin a question, he had opened a drawing box. Kneeling on the carpet, we looked at these fragile footprints and discussed the process of creating them. I had to ask the same questions over and over again because I wasn’t sure I understood it. He had made this gesture which I had to see several times afterwards: that of Saint Veronica holding the veil which had been used to wipe the face of Christ, which had been printed on the cloth. Between his thumbs and forefingers, the other fingers spread out in fan, he held an invisible cloth, which he moved with delicacy. The mystery remained whole, we had agreed to meet again.

So, a few months later, I went up the three steps that led to his workshop, a piece all in length. « Here, it’s like a submarine, on several floors, » he told me. We looked at large leaves full of impacts. Patrice spoke of pictorial fabric and it was the right word, since the drawing cut the weft of the tapestry threads covered the canvas.

The method of manufacture, the process, Patrice spoke of it only with restraint. He didn’t want it to be revealed, or even at the heart of the spectator’s gaze. What he wanted was to search by drawing. « There’s something hidden in my images, something that’s missing. » He quoted Magritte: »I am not looking for the invisible, I am looking for the hidden visible » It was a question of drawing with sand, drawing with a cutter, a roller, and even a torch! « Images, I work them blind. I cover everything and then heat it up with a torch. And then I peel the drawing ». I touched the images of the palm of my hand to feel the granulosity. It was almost like touching light.

Viensvoir: but what do you see in those pictures?

Patrice Pantin: for me, it’s like a sky, a constellation. It floats, it sends out light signals, sounds, crrouik, zzz…

That’s what painting or drawing is: not a construction, but an immersion in a visual environment. Not only visual, by the way: think of Géricault surrounded by body parts while he was working at the Raft of the Medusa. The desire to put something in front of his eyes, to spend whole days there, to get lost. A refuge as much as a quest, a way of escaping danger by hanging out with another.

Viensvoir: it’s a very meticulous and very loose job.

Patrice Pantin: my work tool is finesse. Look, it’s fine as gold leaf. I’m a lacemaker, protected from outside noise. I elaborate an infinitely patient process and at the end, when I put the match on, Pschoutt! I’m pushing the embroiderer inside me! I draw with the heat, something as immaterial as what Bernard Moninot (teacher of drawing at Ensba) uses when he draws with the wind.

We left the drawings to go upstairs: where the famous footprints are made.

« It’s paint itself. An agglomeration of paint on paint. » We were in the middle of metaphysics. And at the same time, it was very concrete, very material. We were palpating rocks, boxes. We even talked about photography: »The relationship with photography is that in my drawings, as in the photo, there is no repentance possible. I hate a painter like Bacon because he keeps going back on what he does, to improve his form. »

Viensvoir: the imprint, the contact, it is also very present at the origins of photography: for example at William Henry Fox Talbot, who called his first photos photogenic drawings.

Patrice Pantin: completely. And my images even have a shimmering side, a bit like the daguerreotype. They must be played in front of the light to see them clearly. It also reminds us of the first images of lunar soil…

Viensvoir: do the stones you use have a symbolic or autobiographical value?

Patrice Pantin: No, I’m interested in starting with nothing. I work with pebbles to make light, floating stones. When I make a stone print, it’s as basic as a grain of sand. But beware, I say basic in the sense that it is an essential element, capable of carrying the infinitely small and infinitely large, the microcosm and the macrocosm. There is only one footprint that is loaded with symbols: it is taken from a Malta stone, which divers brought back to me. It comes from a major tourist attraction on Gozo Island, the Azure Window Arch, which collapsed last year.

These fingerprints are nothing more than a veil of paint sprayed on solid things, stripped off and then positioned flat on a sheet of paper. Something infinitely delicate and volatile, capable of bending at the slightest breath. I see a sort of intermediate layer of the visible. Something reminiscent of Balzac’s fear of photography, who thought he was losing a layer of his personnality every time Nadar took his portrait.

Patrice Pantin: I bring out the other side of things. It’s full and yet it’s empty. Like us, like our bodies: we are full and we are also a lot of emptiness. Like the figure of the ghost that is important to me: a visible surface outside, hollow inside. The sheet can fall to the ground and there’s nothing left.

Patrice gives me a last drawing: »Look at this one, it is very close to failure. There’s something crystallizing, but cracking. »

This intensely poetic encounter ended with an image, when I asked Patrice if he saw an origin to all this, a founding moment. « When I was a kid, at my grandmother’s house, there were these decals that we had to soak in a bowl of water so that the film would come off. It floated, you had to grasp it gently and lay it on your skin… »

Do you know how I recognize an artist, a real one? To the fact that there is always, in a long conversation with him (or her), no matter how loud the discourse on the work (and certainly not the case of Patrice Pantin), a moment of cracking. A blank. A doubt that rushes in brutally and leaves him speechless. Precisely, in our meeting, there was this moment when Patrice turned to me: »but Bruno, tell me if you think I’m wrong, if all this… » He pointed to his works and his hand fell back down the body with a form of sudden downfall. Without this abyss of doubt around which the artist dances, there is no work, only simulacres.