Quand un des maîtres de la photographie se livre sur sa pratique et explique sa démarche photographique : à l’occasion de son exposition »La lumière de l’ombre, photographies des camps nazis » au Musée de la Résistance nationale, Michael Kenna nous dit tout sur sa pratique, ses choix et sa quête profonde.

Alors que l’exposition « La lumière de l’ombre, photographies des camps nazis » rassemblant 82 tirages pour la plupart inédits, se tient sur le nouveau site Aimé-Césaire du MRN, situé à Champigny-sur-Marne (Val-de-Marne), Viens Voir a conversé avec l’auteur, Michael Kenna.

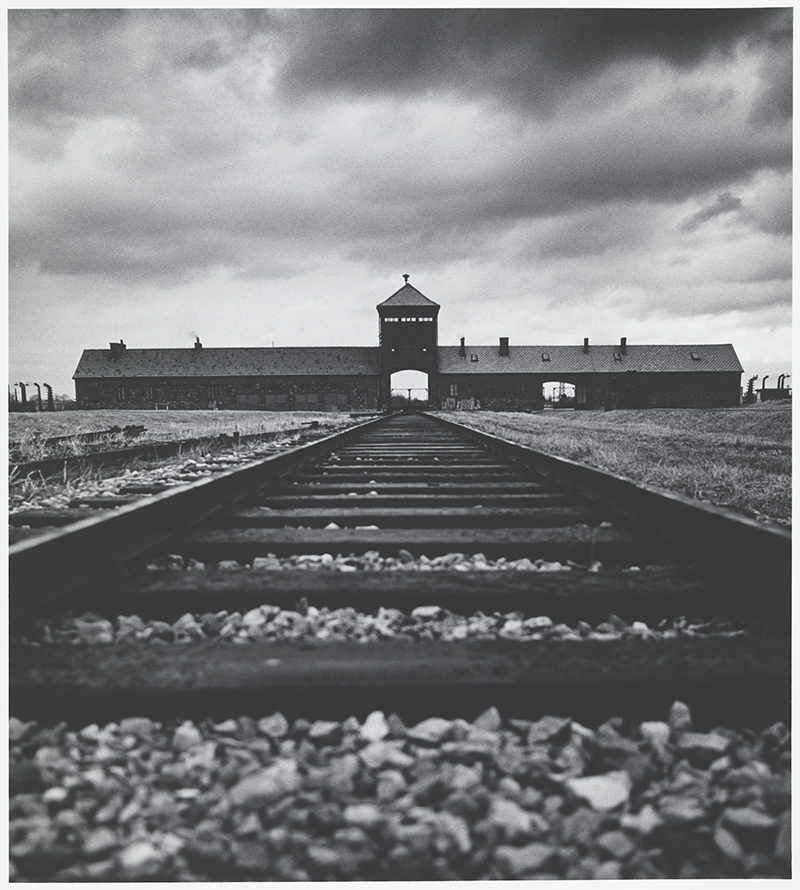

Tout a commencé alors que Michael Kenna était un simple étudiant et pas encore le maître de la photographie mondialement connu qu’il est devenu. Tandis qu’il travaillait dans la chambre noire en compagnie d’un autre étudiant, il vit apparaître dans le bac de développement, la photographie d’une montagne de blaireaux de rasage faisant partie de la muséographie du camp d’Auschwitz-Birkenau. L’émotion qu’il ressentit à la vue de cette photo fut d’autant plus forte que le premier souvenir le liant à son père était précisément lié à l’action du rasage. Il s’engagea alors dans une quête d’une quinzaine d’années, entreprenant à ses frais de nombreux voyages sur les sites des camps de concentration et centres de mises à mort nazis. Depuis, il a fait don au Musée de la Résistance nationale (MRN) d’une partie des matrices résultant de ce travail mémoriel, soit 6 385 négatifs, 6 472 contacts, 1 644 tirages de travail et 261 tirages d’exposition (en 2000 Michael Kenna avait fait don d’une première partie à la Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (MAP), via le Patrimoine Photo).

La suite de l’entretien, ci-dessous, se déroule en anglais.

Why a French institution ?

ViensVoir. Regarding your nationality, why have you chosen a French institution for the donation of your entire work about this international subject ?

Michael Kenna. I don’t have a clear answer to this question, although the one that springs to mind is that France was the first country to ask me for the work! As you probably know, I was born in Northern England and now live in the Pacific North West of USA. Fortunately, I have been able to travel extensively and work on diverse projects in many different countries over my almost five decades of photographing. Looking back, it is accurate to state that I have photographed in France more than in any other country. I suppose I could therefore think of it as a sort of home and a completely appropriate place to donate work.

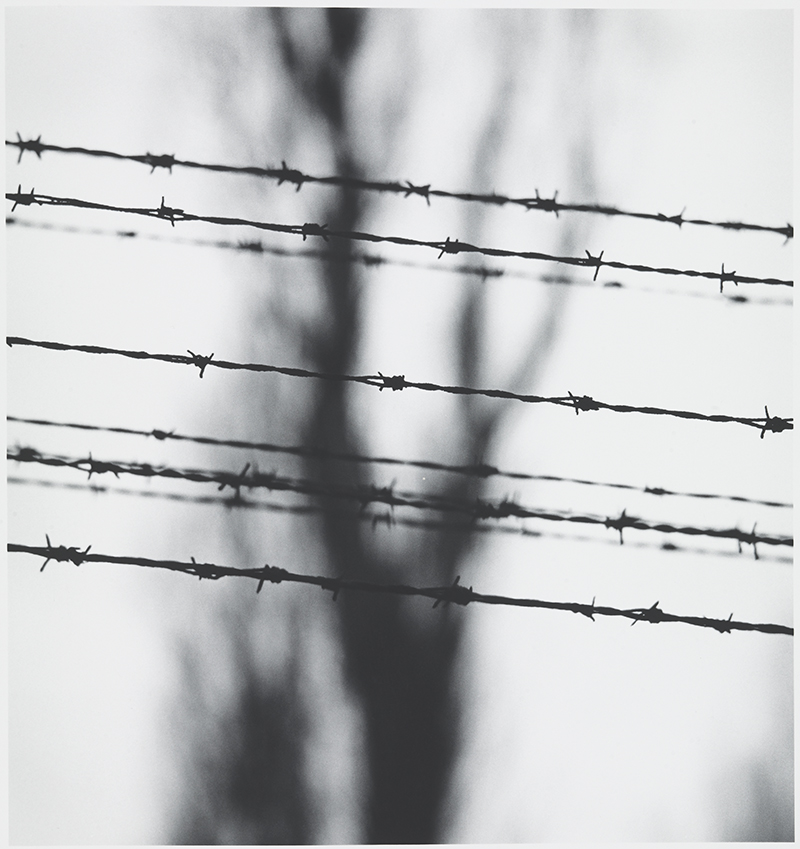

The first concentration camp that I visited, in 1988, was the Natzweiler Struthof camp in France. During those initial years of photographing, I couldn’t understand my own motivation. I almost felt ashamed to photograph these places of horror as I felt that I was in some way taking advantage, whereas I really wanted to make a contribution. Fortunately, fairly early in the project, I made a decision to give all the work away. I distinctly remember photographing the crematorium remains one morning in Birkenau and coming to that conclusion. It felt like I had come to an understanding and agreement with the victims and survivors of this abhorrent massacre. After that, I was more at peace photographing whatever I could find in the camps.

An infinite amount

of photographic possibilities

ViensVoir. You had a first journey and then came back one or two times to the main concentration and death camps (Buchenwald, Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor). Why ? Weren’t you satisfied of your photography or of the weather or did you need more immersion in your subject ?

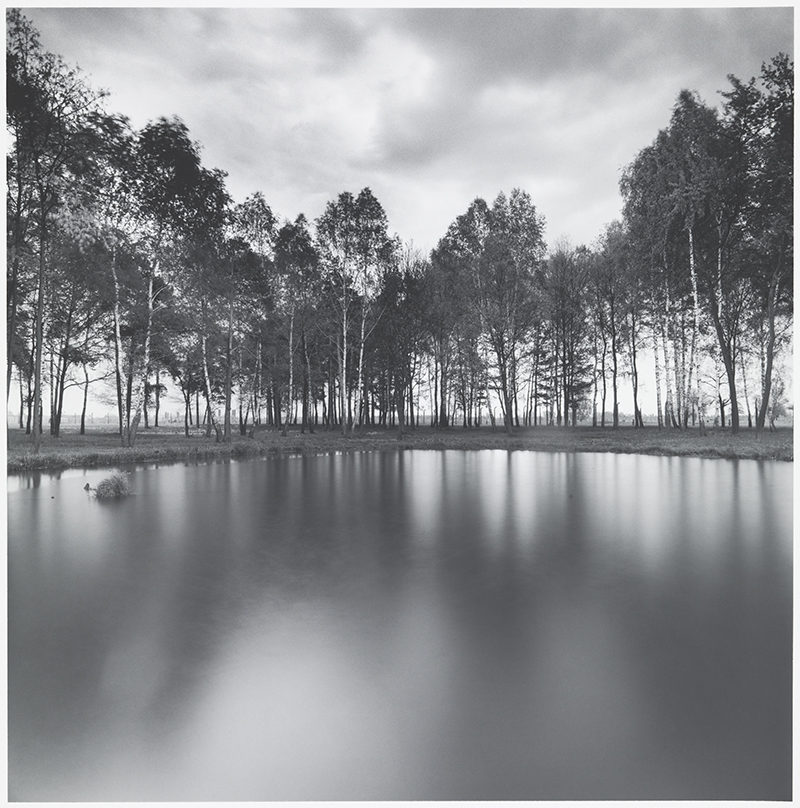

Michael Kenna. It is in the nature of all my work to revisit places as many times as I am able to. I regard the act of photographing to be akin to having a conversation, and therefore a collaboration, with the subject matter. The more times we converse, the deeper and more intimate the conversation becomes. Thoughts, possibilities, detours and deviations arise through an exchange of ideas and energy. I find it is just not possible to cover all the necessary ground in one meeting. I know that as time goes by, as I experience more and get older, I change in subtle and not so subtle ways. In a similar manner, I also observe that subject matter changes – weather conditions, lighting, atmospheric content, they all shift. Nothing ever remains the same, so I feel there is an infinite amount of photographic possibilities. It is in the law of probability that the more time I show up, the more possibilities will be presented to me for fruitful collaborations. Besides, it is enjoyable to renew acquaintances with old friends.

The substantive work

has already been done

ViensVoir. The fact that you have given the whole archive of this project, does it mean that it is over and that you won’t go there anymore (that I cannot believe because it seems that your quest is not only photographic but also spiritual) ?

Michael Kenna. I do not regard any photographic project as ever being truly over, even if the logistics dictate that I do not have the time or possibility to work on them further. If we again use the analogy of conversations – we cannot talk to all the people all of the time. I find it is optimal to be in the present and focus on the person I am with, or the photographic project I am engaged in. Which is not to say that my mind doesn’t constantly flicker back and forth to other people, and other projects. It is the human condition!

I gave my archive in 2000 to the erstwhile Patrimoine photographique in Paris and the Museum of Peace in Caen. Since then, I have revisited a few camps, including Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. Curiously, on these visits I was not able to make what I regard as strong or even interesting photographs. I found myself to be more of a tourist and wasn’t able to fully immerse myself. I now wonder if that was because the places had changed, I had changed, or, more probably, we had both changed. When I was photographing in the late eighties and nineties, I felt more emotionally connected and driven, and the camps themselves were more potently atmospheric, almost as if they had just been liberated. Perhaps as time has gone on, the landscapes in these places have healed somewhat. Most of the camps are now treated more like museums with signage, modernizations, security systems, tour groups, etc. So, yes, I am sure that I will go back to some of these places, but I think the substantive work has already been done.

Documents and catalysts for memory

ViensVoir. I looked at your photographs during a long time and I was surprised to detect many different aesthetics. Some are quite silent (they show very few), others are more spectacular and expressionists, and there are also documentary pics that I did not expect from you. How about the message they convey? And which photographies in this work are your preferred ones (and why)?

Michael Kenna. I sometimes think that photographers choose the projects they work on, and sometimes the projects choose the photographer. In my specific case, I felt chosen to photograph the camps. I was in the right place at the right time with specific photographic training, and I could travel. All my work up to that period was about the relationship, juxtaposition of human built structures and the landscape. I was interested in the memories and traces left behind, whether in old industrial buildings, often derelict, deserted seaside towns, empty parks, stadiums, and other places of activity. I focussed on locations where activities had taken place. The camps loomed large in the journey I was making. I didn’t feel that I had to make conscious decisions on what to photograph or how to photograph, I just made the most of every opportunity I had to photograph whatever I could, in the knowledge that editing decisions could be made later. I think my ultimate personal preference of images is largely irrelevant. What is more important, I feel, is whether any of the photographs touch others, or act as documents and catalysts for memory, for then they will have been well worth the effort of making them.

A memory alive

ViensVoir. Finally: regarding the many travels you have made to those places and I’m sure, the many readings, you must have acquired a real knowledge about those events and this part of History. Why didn’t you want to be involved in the editing and the different choices in the future exhibitions of your work?

Michael Kenna. I think this is again a matter of logistics as much as anything else. I have never felt any sort of possessive ownership of this work and once I made the decision to give it away, it was necessary to relinquish control over it. In this project I regarded myself as a medium or messenger, able to do work to the best of my ability, and then hand it on to others to continue. If I am consulted, of course I am happy to contribute my thoughts and feelings, but, being part of humanity, I enthusiastically endorse and support the participation of others to keep this memory alive.

Nous tenons à remercier grandement Michael Kenna pour sa gentillesse et sa disponibilité, ainsi que son agent, Sabine Troncin-Denis.

L’exposition de Michael Kenna, La lumière de l’ombre, photographies des camps nazis, se tient jusqu’au 15 avril 2022 au Musée de la Résistance Nationale (40, quai Victor Hugo – Champigny-sur-Marne).