English version included below

L’exposition « La folie en tête : aux racines de l’art brut » qui se tient à la Maison de Victor Hugo m’a permis de faire une étrange découverte. Enfin, pas tout à fait une découverte, mais plutôt une redécouverte : une de ces évidences qui crevaient tellement les yeux qu’on avait fini par ne plus lui faire de place.

Mais avant de dévoiler cette évidence, disons combien cette exposition sera enrichissante pour tous les passionnés de l’art brut : ils auront la possibilité d’y voir des oeuvres rares, qui renvoient aux origines de ce qu’on n’appelait pas encore l’art brut. Car à cet instant (celui de leur production), il s’agit surtout d’oeuvres réalisées par des malades mentaux (dans une langue plus allusive, en 1823, le Crichton Royal Hospital se décrit comme un asile pour lunatiques). L’exposition se compose de quatre collections fondatrices pour cette émergence d’un art propre aux patients d’asile psychiatrique, commençant avec celle du Dr Browne (Ecosse) en 1838.

Avec plusieurs questions qui pointent en filigrane : l’artiste brut ne commence-t-il à exister qu’au XIXème siècle ? Ne se développe-t-il que dans ces lieux d’isolement ? Car osons revenir en arrière serait-il, par exemple, impossible d’imaginer un paysan grec de l’Antiquité obstinément affairé à créer de l’art brut, non pour la cité mais pour répondre à sa seule nécesssité intérieure ? C’est comme si l’art brut ne pouvait exister indépendamment de son historicisation et de sa théorisation…

Mais revenons aux oeuvres : certaines impressionnent par leur éminente singularité (c’est l’un des caractères propres aux créations d’art brut), d’autres parce qu’elles préfigurent incroyablement certaines oeuvres entrées dans l’histoire de l’art contemporain : je pense surtout au calendrier de Heinrich Grebing (Collection Prinzhorn), formellement en lien avec l’oeuvre, encore à venir, de Roman Opalka.

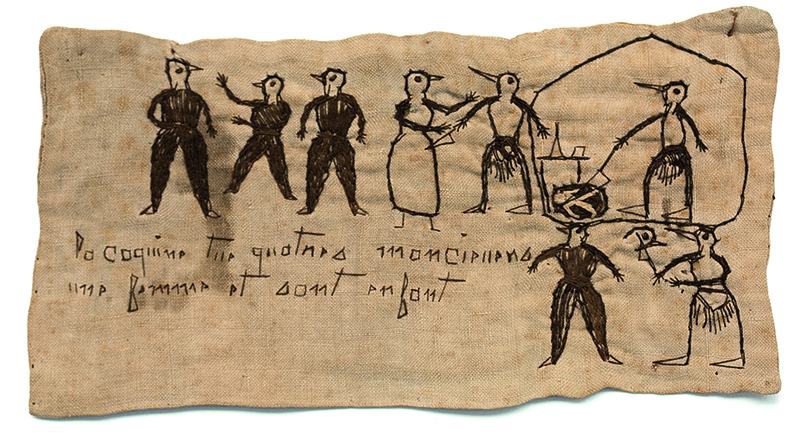

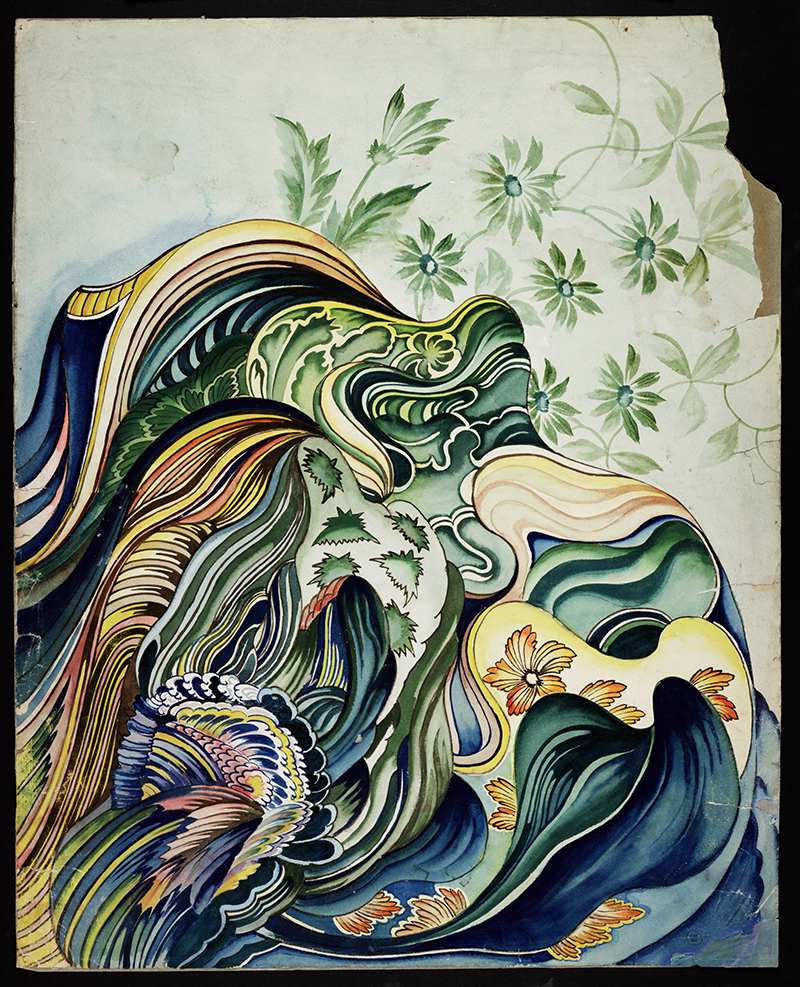

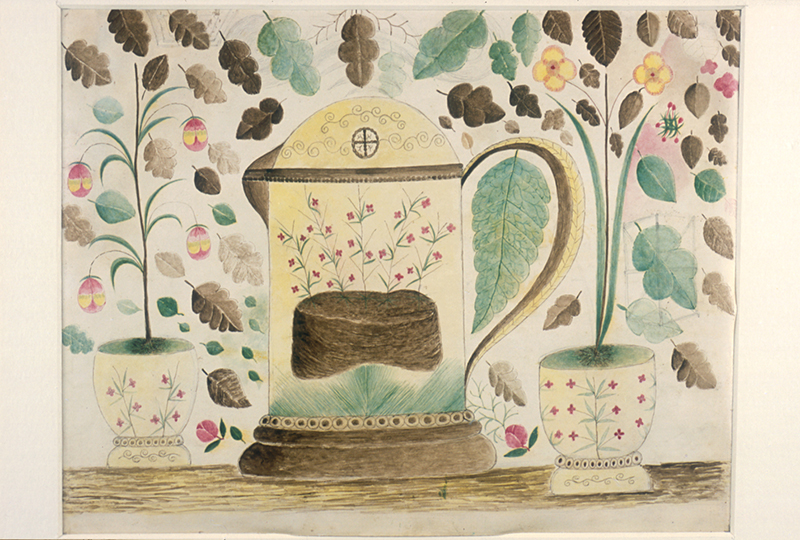

Pourtant, voilà la découverte : si certaines oeuvres sont singulières, d’autres s’inscrivent complètement dans une conception artistique classique, ne visant que les canons de la mimesis. On l’avait oublié. On avait fini par croire que l’aliénation mentale était une voie royale vers la singularité artistique. N’y aurait-il d’ailleurs pas là un joli conte moral : celui d’un individu psychologiquement et socialement affligé, certes, mais qui paie là le prix pour atteindre le montant (compensatoire ?) de son univers artistique. Or, précisément, il y a dans l’exposition plusieurs oeuvres qui sont des tentatives de dessin classique. Maladroites, imparfaites, non virtuoses, mais qui visent la ressemblance, la joliesse, voire même s’inscrivent dans un courant artistique identifié (l’impressionnisme).

Un des mythes de l’art brut prend pour fondement l’absence de culture artistique des auteurs. Mais on sait aujourd’hui qu’au contraire, les patients d’hôpitaux psychiatriques avaient en mains des livres et des magazines reproduisant des images. Comment donc une partie d’entre eux auraient-ils pu échapper au désir premier de reproduire du mieux possible (avec les moyens techniques à leur disposition) l’image vue ? Comment se seraient-ils tous, d’entrée, débarrassés de la volonté d’égaler ce qui était là, devant leurs yeux, plutôt que de plonger dans un univers intérieur singulier ?

Seulement voilà : ces oeuvres, parce qu’elles s’apparentent plus à celles d’amateurs, d’artistes du dimanche, n’offrent que peu d’intérêt au regard des autres. Elles ne révolutionnent pas les médiums, sont plus enfantines que primitives, s’inscrivent dans les catégories plutôt qu’elles ne les bouleversent. Mais surtout, elles parlent d’une approche artistique conventionnelle : or comment l’art brut se satisfairait-il que l’art des malades mentaux se révèle… un art conformiste ! Il me semble pourtant difficile de penser l’art brut sans tenir compte de cette volonté, chez une partie des patients, de s’inscrire dans un art normé. Une sorte d’angle mort presque un peu honteux…

L’exposition « La folie en tête : aux racines de l’art brut » se tient à la Maison de Victor Hugo, 6 place des Vosges, 75004 Paris, jusqu’au 21 mars 2018.

Pour s’initier pas à pas à la naissance de l’art brut et à l’évolution de son histoire, il est recommandé de voir le film d’Arthur Borgnis, Eternity has no door of escape, disponible ici.

English version

Art brut: a strange discovery…

The exhibition « La folie en tête: aux racines de l’ art brut » at the Maison de Victor Hugo allowed me to make a strange discovery. Finally, not quite a discovery, but rather a rediscovery: one of those obvious things that were so obvious that we had finally made no room for it.

But before revealing this evidence, let’s say how enriching this exhibition will be for all those who are passionate about raw art: they will have the opportunity to see rare works, which go back to the origins of what was not yet called raw art. Because at this moment (the one of their production), it is mainly works made by mentally ill people (in a more allusive language, in 1823, the Crichton Royal Hospital describes itself as a haven for lunatics). The exhibition consists of four founding collections for this emergence of an art specific to psychiatric asylum patients, beginning with that of Dr Browne (Scotland) in 1838.

With several questions that stand out as a watermark: does the raw artist not begin to exist until the 19th century? Does it only develop in these isolated places? For, for example, would it be impossible to imagine a Greek peasant farmer from antiquity stubbornly busy creating raw art, not for the city but to respond to its own inner necessity? As if raw art could not exist independently of its historicalization and theorization…

But let us come back to the works: some of them impress with their eminent singularity (one of the characteristics of raw art creations), others because they foreshadow incredibly certain works that have entered the history of contemporary art: I am thinking above all of the calendar of Heinrich Grebing (Prinzhorn collection), formally linked to the work, still to come, of Roman Opalka.

However, here is the discovery: while some works are singular, others are completely in line with a classical artistic conception, aiming only at the canons of the mimesis. We forgot about him. One had come to believe that mental alienation was a royal road to artistic singularity. Moreover, there is not a pretty moral tale here: that of an individual psychologically and socially afflicted, certainly, but who pays the price to reach the amount (compensatory?) of his artistic universe. However, there are several works in the exhibition that are attempts at classical drawing. Dishonest, imperfect, non-virtuoso, but which aim at resemblance, beauty, or even are part of an identified artistic trend (impressionism).

One of the myths of raw art is based on the absence of artistic culture of the authors. But we now know that, on the contrary, patients in psychiatric hospitals had books and magazines reproducing images in their hands. How then could a part of them have escaped the first desire to reproduce the image seen as best as possible (with the technical means at their disposal)? How could they all, from the outset, have gotten rid of the will to equalize what was there before their eyes, rather than plunging into a singular inner universe?

But here it is: these works, because they are more like those of amateurs and Sunday artists, offer little interest to others. They do not revolutionize mediums, are more childish than primitive, fit into categories rather than upset them. But above all, they speak of a conventional artistic approach: how would raw art satisfy itself that the art of the mentally ill is revealed… a conventional art! It seems to me, however, difficult to think of raw art without taking into account the willingness of some patients to follow a standardised art. A sort of almost shameful blind spot…