A l’heure du tout-photographique, la photographie se voit-elle menacée de perdre son sens ?

→ Click here for English version

Si le marché des appareils photos ne se porte pas très bien (lire ici), celui des smartphones commence à présenter lui aussi des signes d’affaiblissement (et ici). C’est que les innovations technologiques ne sont peut-être pas assez significatives pour mobiliser un public déjà bien équipé (et ce, malgré l’obsolescence programmée).

C’est peut-être aussi que, souterrainement, masquée par le tout-selfie et l’enregistrement permanent de nos actes et de nos existences, la photographie ronronne et perd progressivement son sens, un atome infinitésimal après l’autre. Avec elle, nous sommes comme un couple qui se côtoierait de plus en plus sans se rendre compte que pourtant, il s’éloigne.

Ainsi notre quotidien est-il inondé d’images dont la variété n’est qu’apparente, et l’esthétique pré-programmée à coups d’effets et de filtres. Le problème le plus invisible étant que cette photographie subit la miniaturisation propre à nos écrans de smartphones, laquelle réduit nécessairement le nombre d’informations contenues dans l’image, en amenuise la portée sémantique et l’oriente vers une forme d’univocité plus facile à appréhender d’un simple coup d’oeil, alors que la richesse de la photographie s’épanouit dans les images complexes et ambiguës.

Il me semble avoir lu il y a quelques mois qu’un nouveau genre d’appareil photo se préparait à arriver (je dois ici avouer qu’il m’arrive de rêver mes lectures ou les films que j’ai vus, décrivant minutieusement des scènes qui n’y figurent pas). Ce nouveau genre d’appareil aurait pris la forme d’une tablette qu’il suffirait de tourner vers le visible que l’on voudrait enregistrer et qui, sans technologie photographique ni lentille d’objectif, permettrait la formation d’une image. Un pur miroir en quelque sorte.

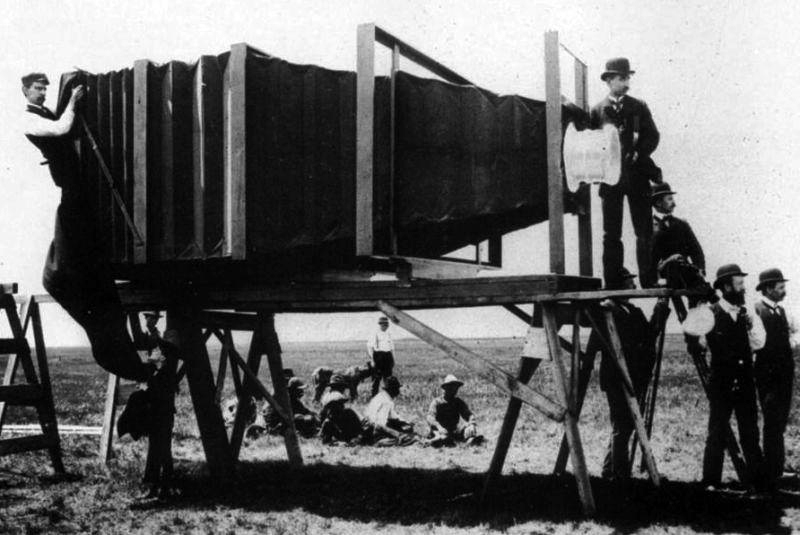

J’ai pensé qu’il y aurait là une sorte de point d’arrivée ultime de la photographie, une manière de boucler la boucle vers ses origines : lorsque j’ai découvert la photo, j’ai souvent imaginé les premiers photographes du XIXème manipulant un tel miroir photosensible.

Et maintenant, un peu de photo-fiction : imaginons les hordes de touristes brandissant de tels miroirs vers la Tour Eiffel, comme une servante égyptienne orientant un miroir de bronze poli pour capter un incertain reflet de la beauté de sa reine. Le peuple de photographes au service des objets qui prendraient alors une juste revanche sur les adorateurs de l’image, l’excès de vision conduisant nécessairement à une forme d’aveuglement.

Mais déjà, bientôt, nous n’aurons plus besoin de coller l’oeil à un viseur trop étroit ni de nous torturer l’esprit avec la composition de la photo puisque, je cite, les appareils photo du futur généreront des images à partir des données environnantes et les assembleront via l’intelligence artificielle, recréant ce qui n’existe pas réellement ou que nous ne pouvons pas voir (on frémit en lisant cela). Ce bientôt est déjà là, ça s’appelle la photographie computationnelle (l’article ici). C’est elle qui nous délivrera de la dangereuse liberté d’interpréter le monde.

La photo s’automatise, le regard aussi. Et désormais, toute la tension de la photographie réside dans la collaboration avec la machine. Que l’on s’y soumette trop et c’est elle qui, insidieusement, prend le contrôle esthétique. Il n’est pourtant pas tant question de résister au programme de l’appareil (lire la thèse vertigineuse développée par Vilem Flusser dans Pour une philosophie de la photographie, selon laquelle toute photographie produite a déjà été prévue par le programme de l’appareil photo) que d’investir en profondeur les images que nous faisons.

Le problème, c’est que des actions correspondant à des degrés d’engagement très différents portent le même nom : Photographie. Depuis le bowl coloré du salad bar jusqu’à une image de Wright Morris en passant par les moustaches de mon chat en gros plan, tout cela s’appelle photographie. En comparaison, l’écriture peut certes être utilisée aussi bien pour une liste de course que pour rédiger A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, mais cela ne nous amène pas pour autant à confondre l’une avec l’autre.

Et là où ça se complique encore, c’est que la réévaluation historique de photos du passé nous pousse, de temps à autre, à complètement chambouler notre système de valeurs. Ainsi, telle photo du passé relevant du snapshot, prise en une fraction de seconde donc certainement pas investie par une intentionnalité artistique, peut se révéler aujourdhui, lue sous une autre lumière (peut-être anachronique), une image d’un puissance esthétique insoupçonnée. Ce renversement des valeurs esthétiques n’est d’ailleurs pas le moindre des intérêts qu’il y a à penser la photographie comme un medium à part. Car la question est celle-ci : là où les autres arts élaborent, la photographie peut atteindre ce qu’elle vise par surprise, par mégarde, par détour. Et la fraction de labeur devient questionnement métaphysique.

Concluons plutôt en filant la métaphore avec l’écriture et la littérature : si toutes les catégories de la photo ont le même droit à exister, il me semble que ce qui est à dégager et valoriser, c’est la pratique d’une écriture photographique qui développe une approche et une pensée du réel.

C’est avec elle que nous écrirons les mots et les précieuses images destinés à nous survivre.

English version

But why photograph?

In the age of all-photography, is photography threatened to lose its meaning?

While the camera market is not in good health, the smartphone market is also starting to show signs of weakening. This is because technological innovations may not be significant enough to mobilize an already well-equipped audience (despite the planned obsolescence).

It is also perhaps that, subterraneanly, hidden by the all-selfishness and the permanent recording of our acts and existences, photography purr and gradually loses its meaning, one infinitesimal atom after another. With it, we are like a couple who would live together more and more without realizing that they are moving away.

Thus, our daily lives are flooded with images whose variety is only apparent, and whose aesthetics are pre-programmed with effects and filters. The most invisible problem is that this photograph undergoes the miniaturization inherent in our smartphone screens, which necessarily reduces the amount of information contained in the image, reduces its semantic scope and directs it towards a form of univocity that is easier to grasp at a glance, while the richness of photography flourishes in complex and ambiguous images.

It seems to me that a few months ago I read that a new kind of camera was about to arrive (I must admit that I sometimes dream of my readings or the films I have seen, meticulously describing scenes that are not in them). This new type of camera would have taken the form of a tablet that could simply be turned towards the visible that one would like to record and which, without photographic technology or an objective lens, would allow the formation of an image. A pure mirror of sorts.

I thought that there would be a kind of ultimate point of arrival for photography, a way of closing the loop towards its origins: when I discovered photography, I often imagined the first photographers of the 19th century manipulating such a photosensitive mirror.

A little bit of photo fiction: let’s imagine now the hordes of tourists wielding these mirrors towards the Eiffel Tower (just revenge of the objects on those who only live for the images), like an Egyptian servant pointing a polished bronze mirror to capture an uncertain reflection of the beauty of her queen.

And soon, we will no longer need to stick our eyes to a too narrow viewfinder or torture our minds with the composition of the photo since « the cameras of the future will generate images from the surrounding data and assemble them via artificial intelligence, recreating what doesn’t really exist or what we can’t see« . This soon is already here, it’s called computational photography. It will deliver us from the dangerous freedom to interpret the world.

The photo becomes automated, so does the look. And now, all the tension of photography lies in the collaboration with the machine. If we are too subjected to the machine, it will, insidiously, takes aesthetic control. However, it is not so much a question of resisting the camera’s program (read Vilem Flusser’s vertiginous thesis, Towards a Philosophy of Photography, according to which any photograph produced has already been planned by the camera’s program) as of investing in depth the images we make.

The problem is that actions corresponding to very different degrees of commitment have the same name: Photography. From the colorful bowl of the salad bar to an image of Wright Morris or my cat’s moustache in close-up, it’s all called photography. In comparison, writing can certainly be used both for a shopping list and for writing A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, but this does not lead us to confuse one with the other.

And where it gets even more complicated is that the historical revaluation of photos from the past pushes us, from time to time, to completely overturn our value system. Thus, a photograph of the past taken in a fraction of a second, and certainly not invested by artistic intentionality, can reveal today, read in another (perhaps anachronistic) light, an image of an unsuspected aesthetic power. This reversal of aesthetic values is not the least of the advantages of thinking of photography as a separate medium. Because the question is this: where other arts develop themselves through work, photography can achieve what it aims for by surprise, by mistake, by detour. And the fraction of labor becomes metaphysical questioning.

Let’s conclude by spinning the metaphor with writing and literature: if all categories of photography have the same right to exist, it seems to me that what needs to be identified and valued is the practice of photographic writing that develops an approach and a thought of reality.

It is with it that we will write the words and images intended to survive us.