(English version included below)

Rapprocher des oeuvres : un exercice difficile mais qui se révèle fertile à la BnF.

Des deux expositions actuellement présentées à la BnF du site François-Mitterrand, l’une consacrée aux Nadar, célèbre famille de photographes, et l’autre élaborant des Conversations avec l’art médiéval (c’est le sous-titre de Make it New), on s’attendrait à ce que cette chronique porte sur la première : prestigieuse somme, aussi richement documentée en photographies et documents d’époque que remarquablement narrée.

C’est pourtant la seconde qui laisse une trace plus profonde, car audacieuse, problématique et pour tout dire, irrésolue. C’est-à-dire, en suspens, ce qui est après tout ce qu’on peut attendre de mieux d’une exposition artistique.

L’exposition Make it New prend pour matière de travail un manuscrit médiéval, La Louange à la sainte Croix, composé entre 810 et 814 par Raban Maur, abbé au monastère de Fulda en Germanie. Si cette période de l’histoire et le découpage du territoire européen est un peu flou, cette courte vidéo se révèlera opportune.

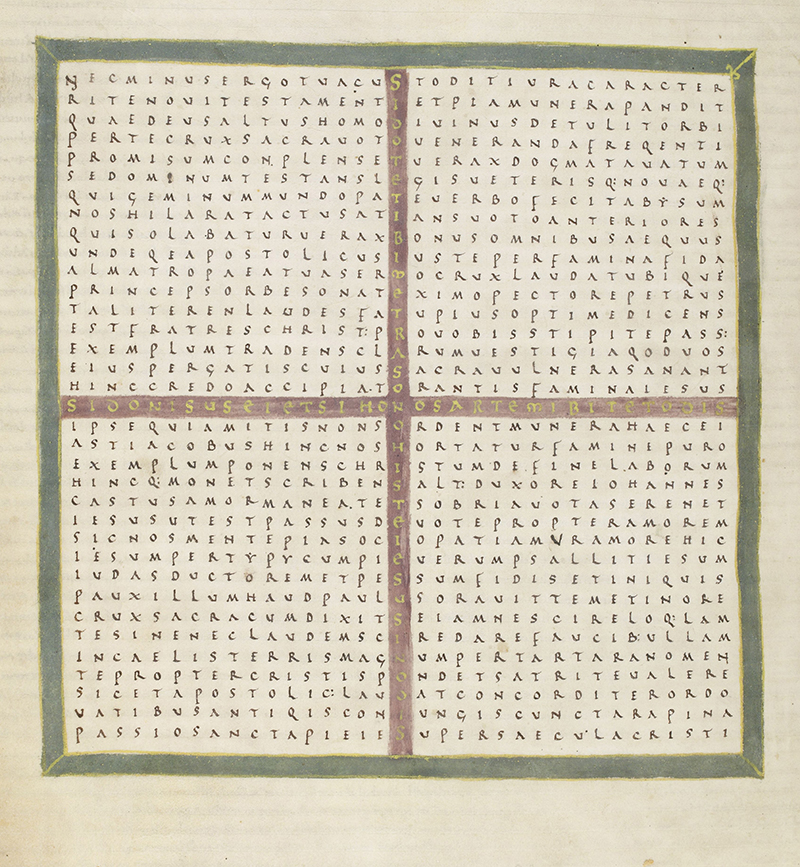

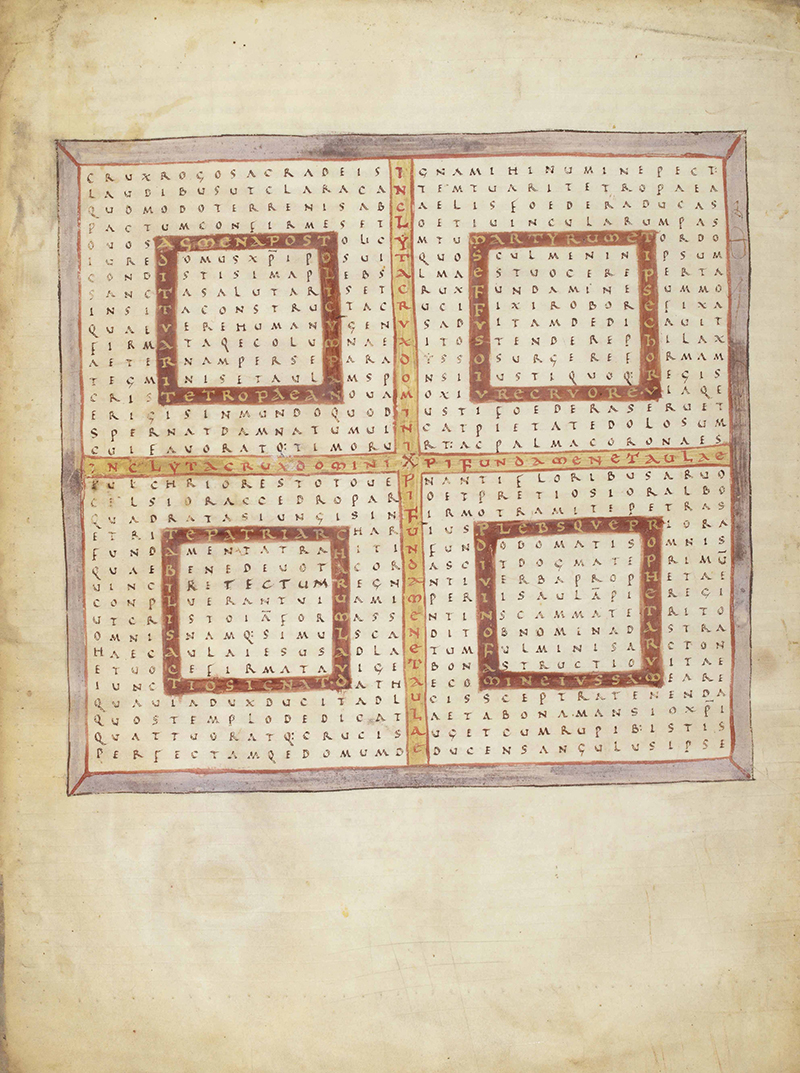

La Louange à la sainte Croix n’est pas un manuscrit comme les autres : ses 28 poèmes s’épanouissent en faisant apparaître des motifs géométriques et chromatiques, mais aussi en suivant des lois mathématiques. On pourrait penser aux contraintes oulipiennes s’il n’y avait pas là un profond codage sensé mettre en relation le divin et la forme de l’univers. L’oeuvre confine au vertige. cet ésotérisme de la forme génère une puissance d’abstraction quasi-intemporelle.

La rapprocher d’oeuvres contemporaines est tentant mais pas si facile. La tâche a été confiée à Jan Dibbets : c’est là que nous retrouvons le lien avec la photographie puisque Jan Dibbets est lui-même photographe (plutôt conceptuel) et qu’il a commissarisé en 2016 une exposition formidablement stimulante, La Boîte de Pandore, au Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (notez qu’à la librairie de la BNF, le catalogue de cette exposition est bradé au prix de 15€ : cadeau !).

Voici donc Jan Dibbets face à ce questionnement : comment faire résonner un art médiéval avec celui d’artistes du XXème siècle, artistes conceptuels, de land art et minimalistes ?

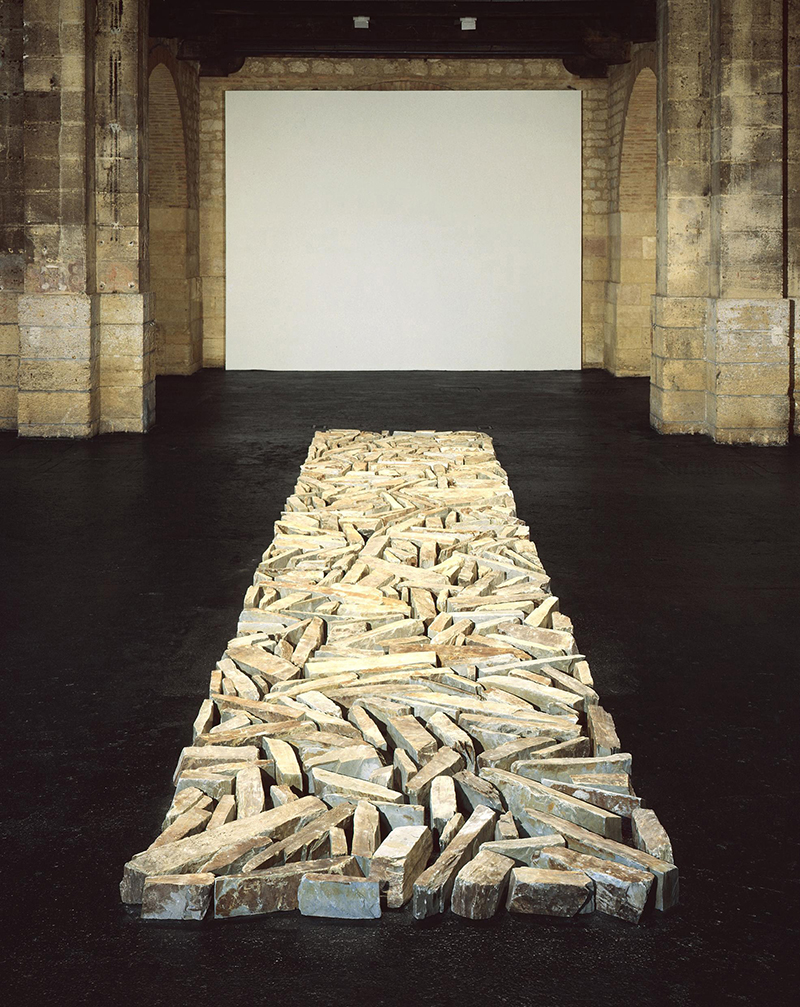

La tâche n’est pas mince si l’on veut éviter des liens trop formels ou trop évidents. Ainsi, le grand commissaire Jean-Hubert Martin, lors de l’exposition Carambolages au Grand Palais, n’avait-il rien carambolé du tout en juxtaposant une dalle funéraire du XIIIème siècle et une sculpture de Carl André ((North Deck). Le rapprochement était trop formel et épuisait son sens en devenant explicite. Pire encore : il secondarisait l’oeuvre contemporaine en lui accolant une prétendue racine, amenuisant ainsi son inscription anthropologique (relire le chapitre anthropomorphisme et dissemblance dans Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde de Georges Didi-Huberman nous éclairera efficacement ).

Rien de tel dans le commissariat de Jan Dibbets, qui, lui aussi, convoque Carl André, en plus de Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, François Morellet, lui-même et quelques d’autres, dans un dialogue dépouillé et silencieux. Pourtant, là aussi, le rapprochement pourrait, au premier regard sembler surtout formel : écho des carrés de Sol LeWitt ou des cercles de Niele Toroni.

Ce serait passer à côté d’une anthropologie de ces formes géométriques élémentaires : carré, cercle, triangle, rectangle étiré dans le sens de la hauteur, sont des formes élémentaires qui ne nous renvoient pas qu’à des signifiés. Elles n’ont pas qu’une valeur symbolique, elles nous conditionnent. Elles ne sont pas que des signes optiques, elles agissent sur notre corps et notre psychisme.

Et c’est pour les laisser agir librement que Jan Dibbets a conçu un espace méditatif, dans lequel les oeuvres oscillent entre la forme élémentaire et sa quasi-disparition. Avec, pour point d’orgue, l’extraordinaire photographie de Jan Dibbets lui-même : presque un monochrome bleu parcouru par des reflets, une légère courbure qui crée une forme de mouvement et en haut à gauche, l’apparition d’un coin noir, comme si le rideau était une page qui allait se tourner. Entre le vide et le plein, l’image du rien ou celle du tout, une image théologique.

English version

A theological image

Bringing works closer together: a difficult but fertile exercise at the BnF.

Of the two exhibitions currently on display at the BnF François-Mitterrand, one devoted to the Nadar, a famous family of photographers, and the other developing Conversations with Medieval Art (it is the subtitle of Make it New), one would expect this chronicle to focus on the first: a prestigious sum, as richly documented in photographs and documents of the period as remarkably narrated.

Yet it is the second that leaves a deeper trace, because it is bold, problematic and, to put it bluntly, unresolved. In other words, in suspens, which is after all the best that can be expected from an art exhibition.

The exhibition Make it New takes as its working material a medieval manuscript, Praise to the Holy Cross, composed between 810 and 814 by Raban Maur, abbot at the monastery of Fulda in Germany. If this period of history and the division of the European territory is a little blurry, this short video (french version) will prove to be interesting.

Praise of the Holy Cross is not a manuscript like any other: his 28 poems flourish by revealing geometric and chromatic motifs, but also by following mathematical laws. One could think of the oulipian constraints if there was not a deep coding that was supposed to connect the divine and the form of the universe. The work borders on vertigo. It has an almost timeless power of abstraction.

Bringing it closer to contemporary works is tempting but not so easy. The task was entrusted to Jan Dibbets: this is where we find the link with photography since Jan Dibbets is himself a photographer (rather conceptual) and that he commissioned in 2016 a tremendously stimulating exhibition, La Boîte de Pandore, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (note that at the BNF bookshop, the catalogue of this exhibition is on sale for 15€ : gift!).

Here is Jan Dibbets facing this questioning: how to make a medieval art resonate with that of 20th century artists, conceptual, land art and minimalist artists?

This is no small task if we want to avoid too formal or obvious links. Thus, the great curator Jean-Hubert Martin, during the Carambolages exhibition at the Grand Palais, had not carambolated anything at all by juxtaposing a 13th century tombstone and a sculpture by Carl André ((North Deck). The rapprochement was too formal and exhausted its meaning by becoming explicit. Worse still: he secondarized the contemporary work by attaching a supposed root to it, thus reducing its anthropological inscription (rereading the anthropomorphism and dissemblance chapter in Georges Didi-Huberman’s Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde will enlighten us effectively).

There is nothing like this in Jan Dibbets’ curating, which also invites Carl André, in addition to Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, François Morellet, himself and some others, into a bare and silent dialogue. However, here too, at first glance, the rapprochement could seem mainly formal: echoes of Sol LeWitt’s squares or Niele Toroni’s circles.

This would be missing an anthropology of these elementary geometric forms: square, circle, triangle, rectangle stretched in the direction of height, are elementary forms that do not only refer us to meanings. They are not only of symbolic value, they condition us. They are not only optical signs, they act on our body.

And it is to let them act freely that Jan Dibbets has designed a meditative space, in which the works oscillate between the elementary form and its near disappearance. The highlight is Jan Dibbets’ own extraordinary photography: almost a blue monochrome with reflections, a slight curvature that creates a form of movement and at the top left, the appearance of a black corner, as if the curtain were a page that would turn. Between the void and the full, the image of nothing or the image of everything, a theological image.