Voyage en art, dans l’atelier de Sylvie Bonnot.

English version included below

Nous nous étions rencontrés sur Unseen, le festival photo d’Amsterdam. Sa galerie hollandaise, The Merchant House, avait fait le lien et nous avions échangé autour d’un thé à la menthe et au miel. Elle m’avait dit que son atelier était en plein coeur de la Bourgogne et j’avais répondu : « dommage, c’est trop loin pour que je vienne ».

Et bien sûr, quelques mois plus tard, nous roulions sur les routes ensoleillées de la campagne charolaise après qu’elle fut venue me chercher en gare de Macon-Loché. On était loin d’Amsterdam mais pour débuter la conversation, elle avait préparé, délicate attention, la même boisson que celle que nous avions partagée là-bas.

Cette visite avait été préparée avec soin : une sélection représentative de ses oeuvres étaient accrochées ou posées contre les murs blancs de l’atelier. Catalogues et portfolios étaient disposés sur la grande table, prêts à être manipulés.

Déjà, dans la voiture, elle avait prononcé ce mot de mue : c’est ainsi qu’elle nomme ses oeuvres, désignant ces fines couches d’émulsion détachées du support, flottant parfois dans l’air. Les Mues, la grande Mue, mue flottante. Le mot revenait sans cesse dans sa bouche. A chaque fois, il faisait naître en moi des images différentes : la peau cassante abandonnée par le serpent, le timbre de l’adolescent qui ne reconnait plus sa propre voix, le mythique continent englouti. A chaque fois qu’elle prononçait le mot, mon esprit voletait et je m’absentais quelques dixièmes de secondes.

Tandis que progressait la conversation, je compris que ce mot ne désignait pas seulement ses oeuvres, mais aussi ce moment de sa vie où elle avait décidé, à 26 ans, de prendre un virage à 180°, renonçant à un avenir confortable dans le secteur bancaire pour s’engager pleinement dans son projet. Il était question d’un texte fondateur, qu’elle avait écrit en une nuit, dans l’urgence, affrontant tous ses questionnements artistiques. S’en était ensuivi l’installation dans cet atelier et la première exposition d’importance, au Salon de Montrouge en 2013.

Et là, plutôt que de photo, c’est de sa pratique du dessin dont nous parlions maintenant.

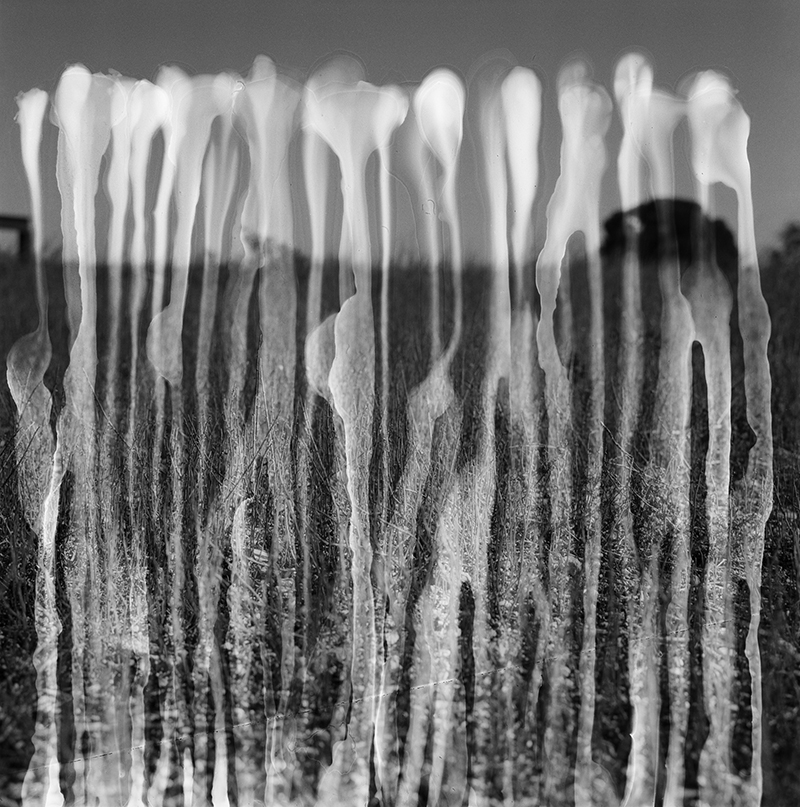

Sylvie Bonnot : Au début, je me posais plus de questions sur le dessin et la peinture que sur la photo. Et j’ai rapidement glissé vers le lien entre photo et dessin. Je cherchais une autre logique que ce qui se passait à la surface de la de la photographie. Comment faire jaillir le dessin sous la photographie ? Alors, j’ai commencé à tracer des lignes en incisant la gélatine. Ce qui m’intéressait et me poursuit toujours, c’est ce qui se passe dans le creux de l’image : les plis, la mue, tout ce qui est fait avec le frissonnement de la gélatine.

Viens Voir : Tu n’as pas peur parfois d’être au bord du décoratif ?

Sylvie Bonnot : Je ne me pose pas cette question. J’ai un rapport chorégraphique avec la lame, c’est comme une danse avec le contenu de l’image, chaque composition nait dans l’instant. Le dessin est censé amener une écriture, une interprétation physique du paysage.

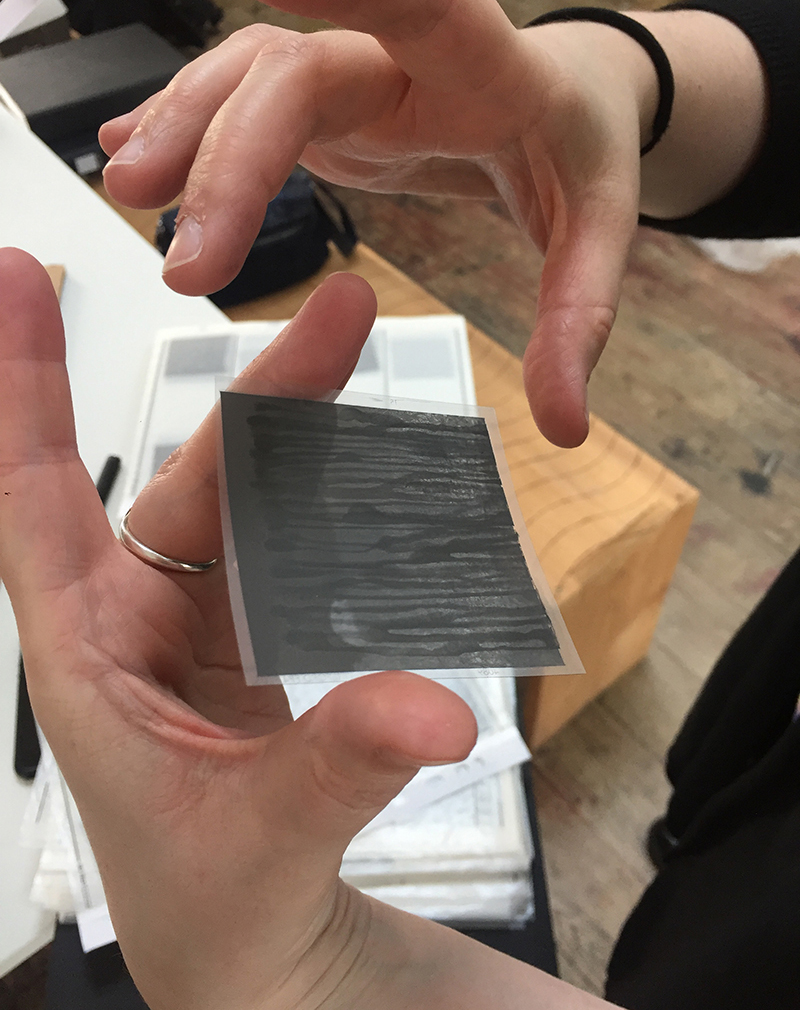

Les premières pièces sur lesquelles nous nous sommes penchés étaient une série de négatifs en moyen format travaillés par diverses interventions plastiques. Elle en a pris un dans sa main. Des coulures pâles sur le paysage. Un lavis. Et toujours ces mêmes gestes de recouvrement, de brouillage de l’image. Une forme sur une autre forme. Une forme sur le réel. Ou plutôt, le réel traversé par une présence. Fantomatique. Photographie spirite.

La matière première, ce sont toujours des photos directes, prises lors de voyages lointains : Hokkaido, Spitzberg, bush australien, transsibérien, comme autant d’expériences intenses ou d’émotions rares. Des photos littéralement habitées. « Car les voyages sont une mise à nu : je m’expose à ce que je vois ».

Des images qui seront réactivées parfois dix ou quinze ans plus tard pour de nouvelles interventions plastiques, lesquelles réaliseront alors pleinement l’image d’origine, donneront toute sa chair à ce qui est représenté là, à la surface. Pour révéler une chose intime, le vivant de l’image.

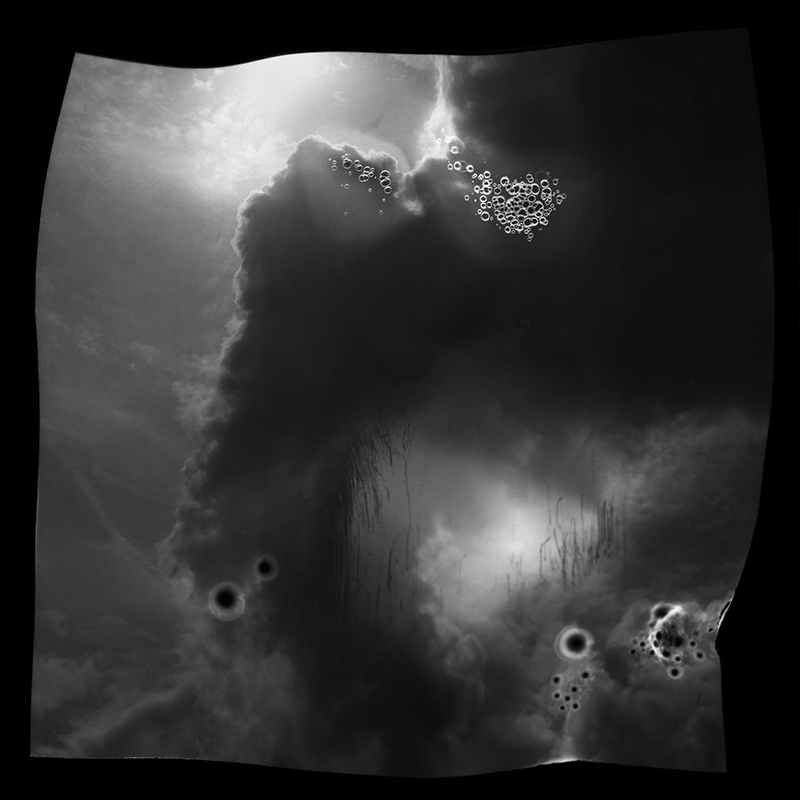

Nous nous penchons ensuite sur une photo posée contre le mur : Firecloud. L’image d’un ciel en décomposition, nuages s’effilochant, surface d’une profondeur estompée, grevée d’impacts. Processus : un négatif brûlé, contracté et sculpté par la chaleur. « Je n’ai pas rephotographié le négatif, je l’ai scanné : pour cela, j’ai construit un caisson autour du scanner, comme un théâtre pour le négatif. Et sur l’image finale, la lumière du scanner s’ajoute à la lumière du soleil. »

Enfin, il y a cette grande mue flottante sur ballon stratosphérique, une commande du CNES. « Une mue, c’est une peau que je détache de l’image pour la poser sur un autre support. Mais ici, le support est fluide, souple. On est presque dans un rapport de peau à peau, dans un principe de dilution de la mue dans son support. »

Viens Voir : Tu fais beaucoup d’essais ? Il y a des ratés ?

Sylvie Bonnot : Oui, la gélatine, c’est une matière vivante ; je l’accompagne, je l’oriente, mais je ne sais jamais si je vais y arriver. Il faut ecouter la gélatine, c’est très sonore. La suite, c’est une chorégraphie, une danse des doigts, très souple, très fluide. Le moment de la dépose demande une vraie plénitude.

On rêve d’assister à de tels instants, qu’elle veut encore garder secrets.

Au fond, peut-être ce mot de mue n’est-il qu’une hyperbole littéraire. Peut-être le terme d’altération photographique, souvent utilisé à propos de la pratique de Sylvie, n’est-il qu’une commodité théorique.

Peut-être que le fond de la chose, c’est que ça vole, qu’on puisse souffler dessus et que ça bouge. Qu’on puisse la travailler à la manière du chaman qui danse et souffle sur l’enveloppe corporelle du mort afin de lui rendre vie. Non pas qu’on ait la naïveté de croire que les morts vont se lever ou que l’image va s’incarner. Ce que l’on croit, plutôt, c’est que les gestes de l’ici et du maintenant vont aider à ouvrir vers un autre monde. Un lieu où les corps retrouvent la vie. Où les images, enfin, se détachent du cadre ou de leur support, qui ne sont parfois rien d’autre que leurs tombeaux.

Oui, que ça s’envole.

Résumons : des expéditions lointaines souvent associées à une forme de prise de risque. Des images qui reposent parfois plusieurs années. Des expérimentations en chambre noire. Mais aussi un rapport poétique avec les mots. Il faut entendre, par exemple, l’émotion avec laquelle Sylvie cite les expressions des ingénieurs en hydraulique qu’elle a accompagnés sur le terrain : corps flottants d’exploitation, exutoire de la galerie de décharge. Et les noms qu’elles donnent à ses séries : les Mues dont on a déjà parlées, ou encore les Ames, images en concrétions, volumes qui saillent hors du mur. Mais alors, où se cache la métaphysique chez Sylvie Bonnot ?

La réponse est dans une dernière photo, une dernière histoire. En feuilletant une publication de ses oeuvres, je suis tombé sur cette pièce : Trou dans la neige.

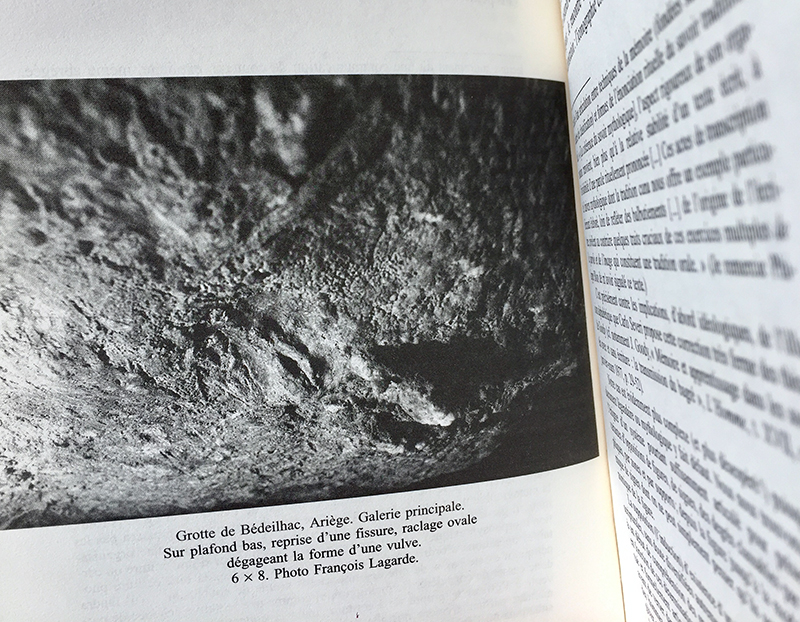

Elle a fait écho à une oeuvre du paléolithique qui est, à mes yeux, un des sommets de l’expression artistique. Je l’ai découverte dans un livre de Jean Louis Schefer, Questions d’art paléolithique (P.O.L, 1999). Au plafond de la grotte de Bédeilhac, en Ariège, une fissure naturelle a été raclée pour dégager la forme d’une vulve.

Comme si la grotte était un ventre de femme, celui de la Terre-Mère ; et comme si les hommes et les femmes du Magdalénien (- 15 000 ans) avaient su discerner là le sexe de la grotte, l’endroit par où communiquer avec le corps de la nature (je pense aussi à certains passages du livre de Michel Tournier, Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique).

Il y a deux mondes.

Le premier est ici, immanent. Il se voit, se touche, se respire et pourtant, si souvent, nous échappe.

L’autre ? Il est de l’autre côté. Derrière la paroi, la nuit, le brouillard. Sous la peau, à l’intérieur du crâne ou dans les étoiles. Un monde d’avant la naissance et peut-être, d’après la vie.

C’est l’art le plus grand, le plus intemporel, que celui qui traque ou fait advenir les portes ou les passages entre ces deux mondes.

Un simple trou dans la neige.

L’artiste en chamane.

Actualités en cours et à venir de Sylvie Bonnot

– Gravité Zéro, Les Abattoirs (Toulouse), jusqu’au 6 octobre

– Des Rives aux Glissements, avec Daphné Le Sergent & Zhu Hong, Centre Culturel de Gentilly – vernissage le 14 juin

– Zones Blanches, commissariat d’Hélène Gaudy, Musée de La Roche-sur-Yon – vernissage le 5 juillet

– Le Baikal Intérieur, exposition personnelle, Le Bleu du Ciel, Lyon – vernissage le 13 septembre

– Remix II, The Merchant House, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas) (exposition collective pendant Unseen)

– La cartographie ou le monde à déchiffrer, octobre 2018, Immixgalerie

English version

Images like passages towards an other world

A journey in art, in Sylvie Bonnot’s studio.

We had met on Unseen, the Amsterdam photo festival. Her Dutch gallery, The Merchant House, made the connection and we exchanged over a mint and honey tea. She had told me that her workshop was right in the heart of Burgundy and I had replied: « pity, it’s too far for me to come ».

And of course, a few months later, we were driving on the sunny roads of the Charolais countryside after she had picked me up at Macon-Loché station. We were far from Amsterdam but to start the conversation, she had prepared, delicate attention, the same drink that we had shared there.

This visit had been carefully prepared: a representative selection of her works were hung or placed against the white walls of the studio. Catalogues and portfolios were arranged on the large table, ready to be handled.

In the car, she had already pronounced this word of Moulting: this is how she calls her works, designating these thin layers of emulsion detached from the support, sometimes floating in the air. The molts, the great molt, the floating molt. The word kept coming back into her mouth. Each time, he gave me different images: the brittle skin abandoned by the snake, the adolescent’s timbre that no longer recognizes his own voice. Every time she said the word, my mind would fly and I would be away for a few tenths of a second.

As the conversation progressed, I understood that this word meant not only her works, but also that moment in her life when she decided, at 26, to take a 180° turn, giving up a comfortable future in the banking sector to fully engage in her project. It was about a founding text, which she had written in one night, in urgency, facing all her artistic questions. This was followed by the installation in this workshop and the first major exhibition at the Salon de Montrouge in 2013.

And there, rather than photography, it is her practice of drawing that we were now talking about.

Sylvie Bonnot : At first, I had more questions about drawing and painting than about photography. And I quickly slipped towards the link between photo and drawing. I was looking for another logic than what was happening on the surface of the photograph. How to make the drawing flow under the photograph? So I started drawing lines by incising the gelatin. What interested me and still pursues me is what happens in the hollow of the image: the folds, the molting, everything that is done with the shivering of gelatin.

Viens Voir: Aren’t you sometimes afraid to be on the edge of some decorative art?

Sylvie Bonnot: I don’t ask myself that question. I have a choreographic relationship with the blade, it’s like a dance with the content of the image, each composition is born in the moment. The drawing is supposed to bring a writing, a physical interpretation of the landscape.

The first pieces we looked at were a series of medium format negatives worked by various interventions. She took one in her hand. Pale drips on the landscape. A lavis. And always these same gestures of recovery, of blurring of the image. One shape on another shape. A form on reality. Or rather, the reality crossed by a presence. Fantomatic. Spiritist photography.

The raw material is always direct photos, taken during distant trips: Hokkaido, Spitzberg, Australian bush, Trans-Siberian, as many intense experiences or rare emotions. Literally inhabited photos. « Because every travel is an exposure: I expose myself to what I see » (Sylvie Bonnot).

Images that will sometimes be reactivated ten or fifteen years later for new artistic interventions, which will then fully realize the original image, will give all its flesh to what is represented there, on the surface. To reveal something intimate, the living image.

Firecloud : the image of a deconstructed sky, clouds fraying, surface of a blurred depth, impacted. Process: a negative burned, contracted and sculpted by heat. « I didn’t rephotograph the negative, I scanned it: for that, I built a box around the scanner, like a theatre for the negative. And in the final image, the scanner light is added to the sunlight. »

Finally, there is this large floating Moult on a stratospheric balloon, a CNES command. « A moult is a skin that I detach from the image to put on another support. But here, the support is fluid, flexible. We are almost in a skin to skin relationship, in a principle of dilution of the molt in its support. »

Viens Voir: Do you try a lot? Are there any failures?

Sylvie Bonnot : Yes, gelatin is a living material; I accompany it, I guide it, but I never know if I will succeed. You have to listen to the gelatin, it’s audible. The sequel is a choreography, a finger dance, very supple, very fluid. The moment of the deposit requires a real plenitude.

We dream of witnessing such moments, that she still wants to keep secrets.

At heart, perhaps this word « moult » is only a literary hyperbole. Perhaps the term « photographic alteration », often used about Sylvie’s practice, is only a theoretical convenience.

Maybe the root of the problem is that it flies, that you can blow on it and it could move. May it be worked in the manner of the shaman who dances and blows on the body envelope of the dead in order to give it life. Not that we have the naivety to believe that the dead will rise or that the image will be incarnated. What we believe, rather, is that the actions here and now will help open another world. A place where bodies find life. Where the images, finally, stand out from the frame or their support, which are sometimes nothing other than their tombs.

Yeah, let it fly.

Let’s summarize: distant expeditions often associated with a form of risk taking. Images that sometimes rest several years. Darkroom experiments. But also a poetic relationship with words. It is necessary to hear, for example, the emotion with which Sylvie quotes the expressions of the hydraulic engineers she accompanied in the field: « floating operating bodies », « outlet of the discharge gallery ». And the names she give to her series: the Mues we have already talked about, or the Souls, images in concretions, volumes that protrude from the wall. But then, where is Sylvie Bonnot’s metaphysics hidden?

The answer is in one last picture, one last story. While leafing through a publication of her works, I came across this piece: Trou dans la neige ( A hole in the snow).

It echoed a Paleolithic work which is, in my opinion, one of the heights of artistic expression. I discovered it in a book by Jean Louis Schefer, Questions d’art paléolithique (P.O.L, 1999). On the ceiling of the cave of Bédeilhac, in Ariège, a natural crack was scraped to clear the shape of a vulva.

As if the cave were a woman’s belly, that of Mother Earth; and as if the men and women of the Magdalenian (-15,000 years) had been able to discern there the sex of the cave, the place by which to communicate with the body of nature (I also think of certain passages from the book by Michel Tournier, Vendredi or the Limbo of the Pacific).

There are two worlds.

The first is here, immanent. We can see it and touch it, and yet, so often, it escapes us.

The other one? He’s on the other side. Behind the wall, behind the night, through the fog. Under the skin, inside the skull or in the stars. A world before birth and perhaps, after life.

It is the greatest art, the most timeless, that hunts down or makes happen the doors or the passages between these two worlds.

A simple hole in the snow.

The artist as a shaman.