Le corps-paysage ou le vertige de l’analogie, extrait du cours Une autre histoire de l’art.

(English version included below)

Alors que s’achève la saison 2 du cycle Une autre histoire de l’art, présenté à la Galerie Binome et que j’ai consacré cette année à la notion de paysage, j’aimerais en partager un extrait.

Celui-ci est révélateur d’une méthode de travail, plus portée sur le cheminement à travers des oeuvres, des époques, des pratiques et des supports artistiques, que sur une progression chronologique et compartimentée. Appelons ça une transversalité féconde.

Posons les bases : le paysage n’est pas un objet qui se constitue de manière autonome, attendant la présence de l’observateur, au détour d’un sentier ou face au balcon panoramique. Il est tout aussi exagéré d’affirmer que le paysage n’a aucune existence indépendamment du spectateur. Disons alors qu’il est le résultat d’une série d’échanges. Echanges entre ici et là-bas, entre le moi intérieur et le monde extérieur, entre le présent de ma position (mon point de vue) et l’horizon, qui dessine un futur. Ce n’est pas le moindre intérêt de ces échanges que d’ouvrir sur des correspondances et des jeux d’échelle.

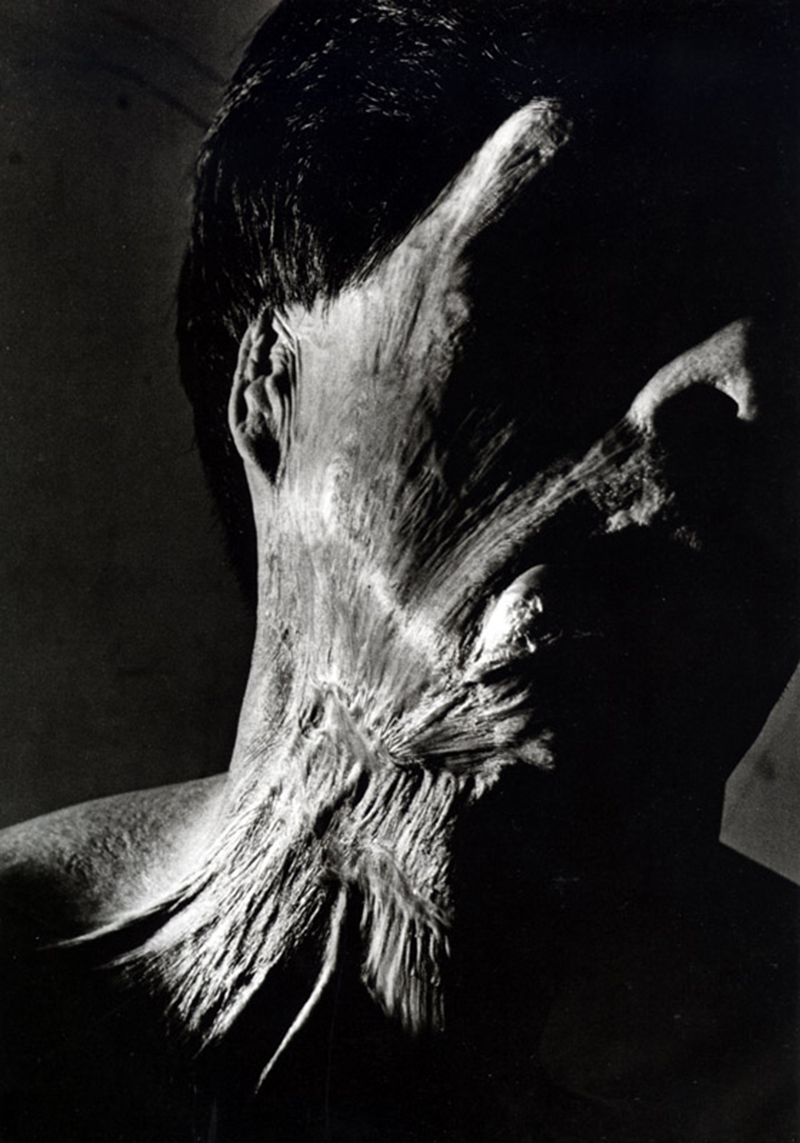

Les voici totalement à l’oeuvre dans cette très saisissante photographie d’Isabelle Chapuis, extraite de sa série « Eloge du Vivant ».

Un dos envahi par un naevus géant (rappelons qu’un naevus, nom savant du grain de beauté, n’est pas une maladie mais un particularisme de la peau et qu’il est, dans de tels cas, congénital).

Le déhanchement élégant, la résonance avec les essences de bois du fond et de la planche sur laquelle est assise le modèle (Agathe), la chevelure soigneusement lissée vers l’avant : tout concourt à décharger l’image de ce qui pourrait évoquer la souffrance ou générer une forme de répulsion, visible dans les photographies de peaux irradiées suite aux explosions nucléaires au Japon, à la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale. Tendue à craquer, la peau y apparaît en voie de pétrification, un devenir-statue.

Ici, la photo appelle presque le toucher : une cartographie très intime, avec ses reliefs, ses plissements, ses cratères et ses méandres. Un monde, une planète, presque une galaxie si le regard descend le long des reins et rencontre quelques taches, comme autant d’astéroïdes isolés, dont certains laissent échapper quelque pilosité, écho de la chevelure de Bérénice. Le champ métaphorique paraît infini, l’emphase presque un peu facile.

La démarche est pourtant révélatrice d’une forme de pensée et de vision du cosmos. Celle-ci se base sur une recherche de correspondances entre les différents éléments du monde, une forme de pensée analogique particulièrement à l’oeuvre dans le monde médiéval (la pensée alchimiste en est une survivance) et à la Renaissance. Ainsi Léonard de Vinci, dans son Traité de la Peinture, compare-t-il l’homme à la terre :

« Si l’homme a les os, support et armature de la chair, le monde a les rochers comme supports de la terre ; […] si l’homme porte le lac du sang où le poumon se gonfle et dégonfle dans la respiration, le corps de la terre a son océan qui, lui, croît et décroît toutes les six heures en une respiration cosmique ; […] si les veines partent de ce lac de sang, en se ramifiant dans le corps humain, de même l’océan remplit le corps de la terre d’une infinité de veines d’eau. »

L’homme est un paysage, tandis que la terre n’est qu’un grand corps : microcosme et macrocosme s’échangent.Une idée que l’on retrouve dans de nombreux mythes, le corps démembré d’un être primordial donnant naissance aux différents éléments du cosmos (P’an-ku dans la mythologie chinoise, le géant Ymir dans la mythologie scandinave, Purusha dans les Veda hindous).

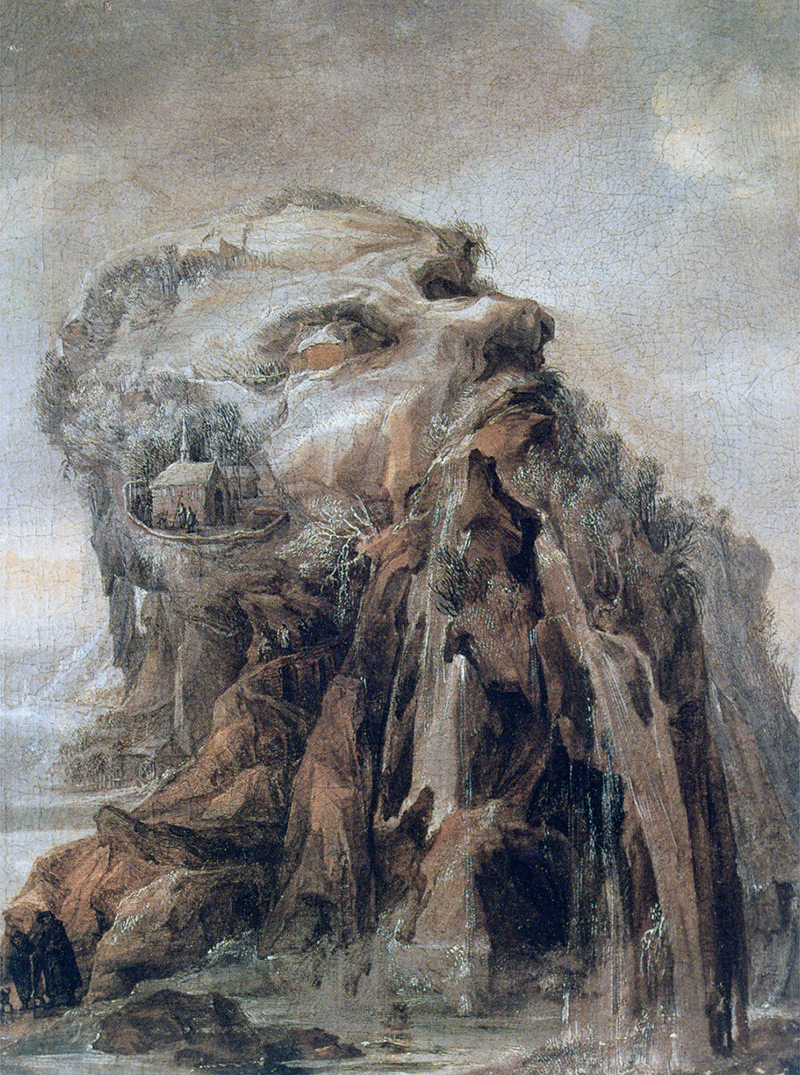

Cette vision d’un monde communiquant à ses différentes échelles est particulièrement sensible dans la série de paysages anthropomorphiques des quatre saisons du flamand Joos de Momper (1564-1635). Une approche qui n’est pas sans évoquer celle, plus connue, d’Arcimboldo, mais dont on néglige trop souvent les dimensions symboliques (ici les âges de la vie humaine) et allégoriques pour n’en retenir que la prouesse visuelle. Le paysage anthropomorphique réenchante la nature et déploie tous les ressorts de l’image cachée (un passionnant panorama de cette pratique présentée par Jean-Hubert Martin).

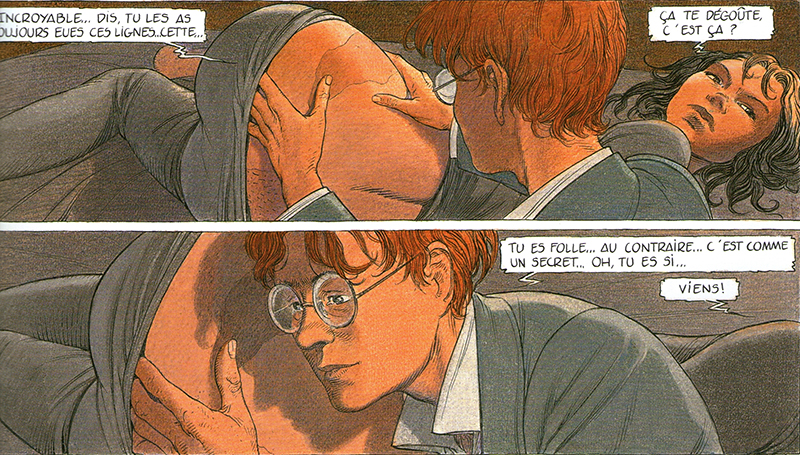

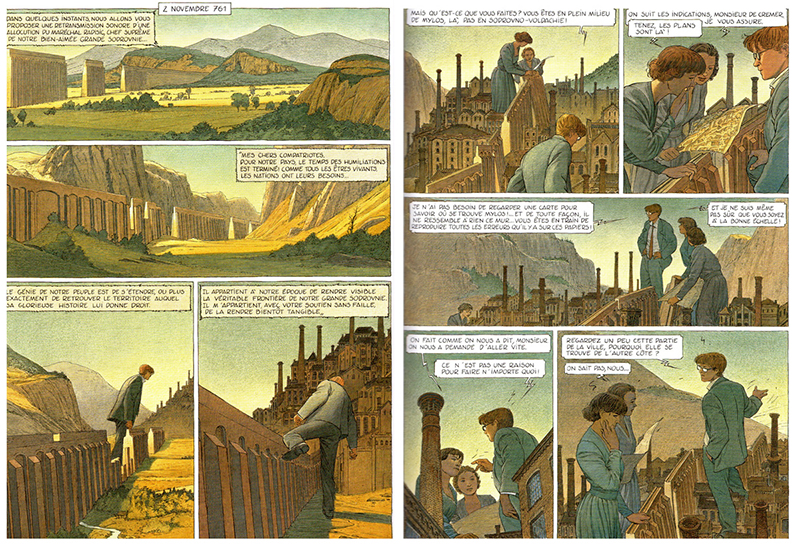

Une très belle bande dessinée de Luc Schuiten et Benoît Peeters, parue en 2004 chez Casterman se fait l’écho de ces thématiques. Dans « La Frontière Invisible », Roland, jeune recrue du Centre de Cartographie de Sodrovno-Voldachie, se trouve pris dans la toile d’un jeu de correspondances qui tisse ensemble l’échelle réelle du paysage, celle de la carte exacte ou fantasmée à laquelle il travaille, une tache qui pointe sur le bas du dos de sa belle… Secret du monde ou pur délire de la pensée analogique ?

Pour avoir la réponse, ou vous perdre un peu plus, il vous faudra lire la suite de l’histoire, entrer dans le paysage, et vous en approcher jusqu’à le perdre de vue.

S’en approcher ? Ecoutons les mots d’Agathe, la jeune femme dont le dos ouvre cet article : « La peau est une limite. La mienne n’est pas tout à fait acquise, et c’est pour ça que je cherche quelque chose en l’autre. Sans me mettre à sa place, j’essaye de ressentir en lui ce que je n’arrive à ressentir en moi, de me reconnecter à quelque chose qui est mort, froid, déshumanisé, resté trop longtemps dans sa cachette. Il faut que je trouve une chaleur dans la peau de l’autre. »

C’est bien ça : le paysage comme suite d’échanges entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur.

Pour voir plus d’images d’Isabelle Chapuis, c’est ici

English version

Landscape drifts

The body-landscape or the vertigo of analogy, excerpted from the course Another History of Art.

As Season 2 of the Another Story of Art series, presented at Galerie Binome and devoted this year to the notion of landscape, I would like to share an excerpt from it.

This is indicative of a working method that is more concerned with the progression through works, epochs, practices and artistic supports than with a chronological and compartmentalized progression. Let’s call it a fertile transversality.

Let’s lay the foundations: the landscape is not an object that is formed autonomously, waiting for the presence of the observer, at the bend of a path or in front of the panoramic balcony. It is equally exaggerated to say that the landscape has no existence apart from the spectator. Let us say then that it is the result of a series of exchanges. Exchanges between here and there, between the inner self and the outer world, between the present of my position (my point of view) and the horizon, which shapes a future. It is not the least interest of these exchanges to open up on correspondences and games of scale.

Here they are totally at work in the very striking photograph of Isabelle Chapuis, taken from her series « Eloge du Vivant ».

A back invaded by a giant nevus (remember that a nevus, the learned name of the mole, is not a disease but a particularity of the skin and that it is congenital in such cases).

The elegant swaying, the resonance with the woods of the back and the board on which the model is sitting (Agathe), the hair carefully smoothed forward: everything helps to unload the image of what could evoke suffering or generate a form of repulsion, visible in the photographs of irradiated skins following the nuclear explosions in Japan, at the end of the Second World War. Tended to crack, the skin appears there in the process of petrification, a becoming-statue.

Here, the photo almost calls for touch: a very intimate cartography, with its reliefs, folds, craters and meanders. A world, a planet, almost a galaxy if the gaze descends along the kidneys and encounters some spots, like so many isolated asteroids, some of which let out some hair, echo of Berenice’s hair. The metaphorical field seems infinite, the emphasis almost an easy one.

However, the process reveals a form of thought and vision of the cosmos. This is based on a search for correspondences between the different elements of the world, a form of analogical thought, particularly in the medieval world (the alchemist thought is a survival) and in the Renaissance. Thus Leonardo da Vinci, in his Treatise on Painting, compares man to the earth:

« If man has the bones, support and framework of the flesh, the world has the rocks as supports of the earth;[…] if man carries the lake of blood where the lung swells and deflates in breathing, the body of the earth has its ocean which, on the other hand, grows and decreases every six hours in a cosmic breathing….] if the veins depart from this lake of blood, branching into the human body, so the ocean fills the earth’s body with an infinite number of water veins. »

Man is a landscape, while the earth is only a great body: microcosmos and macrocosms are exchanged.An idea found in many myths, the dismembered body of a primordial being giving birth to the different elements of the cosmos (P’ an-ku in Chinese mythology, the giant Ymir in Scandinavian mythology, Purusha in Hindu Veda).

This vision of a world communicating at its different scales is particularly sensitive in the anthropomorphic landscape series of the Flemish Joos de Momper’s four seasons (1564-1635). This approach is reminiscent of Arcimboldo’s more well-known approach, but all too often the symbolic (in this case the ages of human life) and allegorical dimensions are neglected to retain only its visual prowess. The anthropomorphic landscape re-enchant nature and unfolds all the springs of the hidden image.

A very beautiful comic strip by Luc Schuiten and Benoît Peeters, published in 2004 by Casterman, echoes these themes. In « La Frontière Invisible », Roland, a young recruit from the Sodrovno-Voldachie Cartography Centre, finds himself caught in the canvas of a correspondence game that weaves together the real scale of the landscape, that of the exact or fantasized map he is working on, a stain that points to the lower back of his beautiful girlfriend… Secret of the world or pure delirium of analogical thought?

To get the answer, or lose yourself a little more, you’ll have to read the rest of the story, get into the landscape, and get close to it until you lose sight of it.

Getting close? Let us listen to the words of Agathe, the young woman whose back opens this article: »The skin is a limit. Mine isn’t entirely taken for granted, and that’s why I’m looking for something else. Without putting myself in his shoes, I try to feel in him what I cannot feel in me, to reconnect with something which is dead, cold, dehumanized, and has remained in his hiding place for too long. I have to find a warmth in each other’s skin. »

That’s right: the landscape as a consequence of exchanges between inside and outside.